Free trade agreements

Worried about Central American emigration? Consider trade policy

Published 10 October 2023

Though trade agreements aim to expand trade, there are often huge divergences in their effects. Stringent requirements in a free trade agreement with the US, for instance, actually led to a 58% contraction of apparel exports for Central American countries. Reform of the agreement may be necessary for expanding economic opportunity and job creation, which would in turn address the root causes of Central American migrant workers heading, often illegally, into the US.

Immigration, especially along the U.S. southern border, is a potentially divisive issue for the 2024 election. Rising immigration from Central America has been a key policy concern since before the COVID-19 pandemic. The Biden administration says that the long-term solution is to address the root causes of Central American migration.

Since 2021, President Joe Biden has highlighted addressing such immigration by promoting economic opportunity. Vice President Kamala Harris’ May 2021 ‘Call to Action to the Private Sector to Deepen Investment in Northern Central America’ builds on the president’s ‘Plan to Build Security and Prosperity in Partnership with the People of Central America’. In July 2021, Vice President Harris laid out the private-sector, investment-focused ‘US Strategy for Addressing the Root Causes of Migration in Central America’.

Though security and corruption are often listed as leading factors driving migrants, the lack of economic opportunity remains at the top of the concerns for most migrants. Expanding economic opportunity, especially in form of creating “good” jobs, is the best way to address the causes of Central American migration.

There is strong evidence that manufactured goods exports create jobs for people who would otherwise be unemployed, or remain in the informal sector or in subsistence agriculture. These are the people who emigrate in search of greater economic opportunities across the border.1 Since the 1990s, developing countries have pursued trade agreements in hope of expanding exports and promoting economic development. Such agreements have generally done so. Since 2000, developing country exports have been associated with falling poverty, falling inequality, and economic growth in developing countries. Over the last quarter-century, trade agreements have recently added trade-related intellectual property rights, cross-border capital flows, investment dispute settlement procedures, and harmonizing regulatory standards besides reducing barriers to trade.2

Though trade agreements expand trade, they are not a cure-all panacea. In fact, most current “free trade” agreements do not actually result in “free” trade. Reviews of trade agreements find huge divergences in the effects of trade agreements.3 About half of all trade agreements have no significant effect and only about a quarter of them increase trade.4

The increasing complexity and depth of trade agreements have created barriers to trade. They must be reformed to expand exports while simultaneously supporting worker rights and improving working conditions. Identifying these “deep” barriers to trade is an important first step toward potentially relaxing these barriers to induce reforms that make trade beneficial for workers in exporting countries and, by extension, workers in the United States. The second step is to accurately relax these barriers in ways that actually create mutual gains.

Since expanding Central American exports would create jobs and reduce Central American emigration, the logical first place to start is with the trade agreement between the United States and Central America (including the Dominican Republic), the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). CAFTA-DR became effective in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and the United States in 2006. The Dominican Republic joined in 2007 and Costa Rica in 2009. The terms of the agreement include trade liberalization, customs administration, and trade facilitation.5 The United States aimed to promote “Made In America” jobs, improve workers’ rights and conditions, and foster growth and stability in the region. CAFTA-DR was also expected to boost market opportunities for US textile and apparel manufacturers.

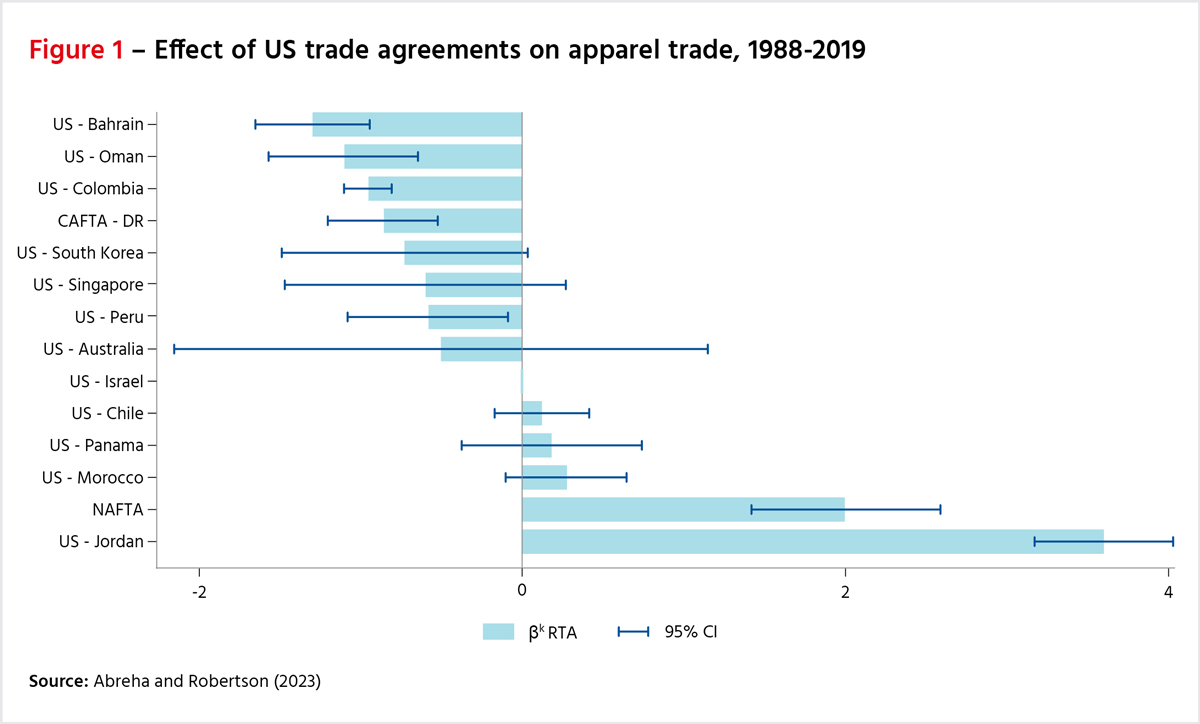

Apparel is the main manufactured export from Central America, directly supporting nearly 500,000 jobs. Using bilateral trade flows, our research found that more restrictive rules of origin (RoOs) are associated with less trade, and apparel RoOs are especially restrictive. Figure 1 plots the estimated effect of US trade agreements on the apparel trade. The estimated contraction in trade for CAFTA-DR suggests that apparel exports are about 58% less compared with what trade levels would have been without the agreement. By contrast, the US-Jordan agreement, which does not have a yarn-forward rule6 and requires at least 35% regional content, has a positive and large effect: a 3,567% rise. Similarly, the US-Morocco agreement brought a 32% increase, perhaps because it has a long phase-in period with large exception levels.7 The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is associated with an increase in apparel trade of about 640%.

Source: Abreha and Robertson (2023).

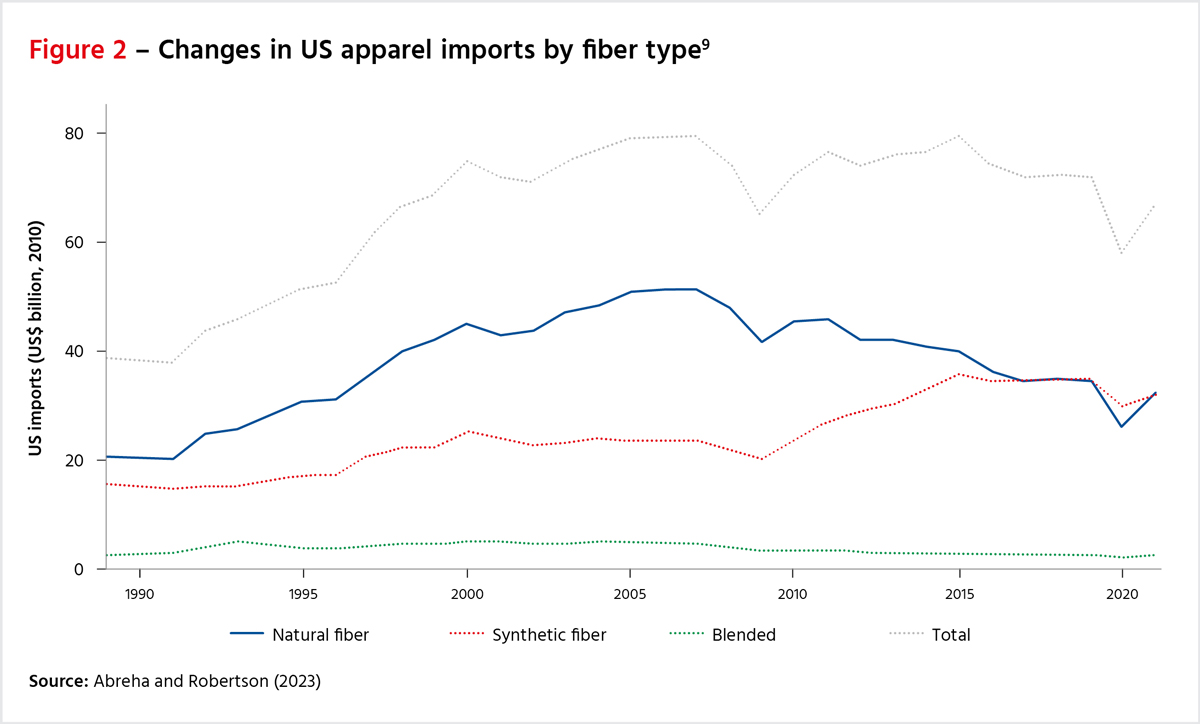

Revising CAFTA-DR is necessary because clothing technology has changed. Over the last 20 years, the range of fibers, threads, and fabrics used in modern clothing has expanded. Being able to use new inputs is critical for expanding production. Figure 2 shows the rising importance of artificial fibers in US apparel imports. Allowing Central America to expand its use of artificial fibers would create domestic demand that would attract investment into the region to produce those fibers, thread, and fabrics.8

Source: Abreha and Robertson (2023).9

Revising the apparel RoOs would create jobs in Central America. The CAFTA-DR apparel trade estimate allows us to heuristically approximate the number of jobs that could be created by relaxing CAFTA-DR’s restrictive RoOs. These estimates suggest that, on average, trade agreements increase apparel trade by 45%. This implies that if we were to renegotiate CAFTA-DR so that it resembles the average agreement, trade would increase by 103%, or more than double the current apparel trade level.

The effect on employment depends on the strength of the relationship between exports and employment. Apparel is labor-intensive, so this relationship would be relatively high, but, to be conservative, we use United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates for the labor intensity of gross exports that range from 0.47 to 0.53, calculated as a ratio between labor and merchandise export value-add.10 These estimates suggest that a 10% increase in exports would increase employment by about 5%. In our case, relaxing RoO could increase exports by 103%, which would, according to the UNCTAD estimates, result in a 51.5% increase in employment. Assuming half a million current employees in the apparel sector of Central America, we might expect an increase of about 257,500 jobs, not counting the indirect jobs created through additional consumption spending by workers and services for the expanding industry. In 2023, US Customs and Border Protection reported 383,504 encounters at the US southwestern border with people from northern Central America (Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador).11 Adjusting CAFTA-DR’s RoOs could reduce migration by at least 67% if would-be migrants took new Central American apparel jobs instead.12

The potential gains from relaxing the CAFTA-DR RoOs create a powerful incentive for Central American governments. This incentive could in turn impel measurable improvements in freedom of association, collective bargaining, and working conditions in Central America. In addition, the possibility of relaxing RoOs could also include a requirement of demonstrated and measured increases in the purchases of inputs from the United States to promote job creation in the US textile industry. Economic models show that expanding the range of inputs induces the entire industry to expand, which suggests that the demand for US inputs could also expand as the Central American apparel industry expands. Revising the CAFTA-DR trade agreement has, therefore, the potential to promote economic growth, expand employment, and create incentives to induce worker-friendly reforms in Central America.

***

[1] The East Asian miracle: economic growth and public policy: Main report (English), The World Bank: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/975081468244550798/main-report

Does Trade Cause Growth?, The American Economic Review: https://www.jstor.org/stable/117025

Trade raises income: a precise and robust result, Journal of International Economics: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022199604000169

[2] What Do Trade Agreements Really Do?, Journal of Economic Perspectives: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/jep.32.2.73

[3] Chapter 3-Gravity Equations: Workhorse, Toolkit, and Cookbook, ScienceDirect: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780444543141000033

[4] Do we really know that trade agreements increase trade?, SPRINGER LINK: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10290-014-0188-3

[5] Globalization, Wages, and the Quality of Jobs: Five Country Studies, World Bank: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/epdf/10.1596/978-0-8213-7934-9

[6] Rules of origin usually require a single transformation to qualify for agreement benefits. Single transformations are often measured by a change in value, a change in product classification, or applying a technological process that would generate a significant change in inputs. For apparel, the move from cut fabric into a garment would be a single transformation. The “yarn-forward” criterion requires that the fabric that produces the pieces to be sewn and the yarn that goes into the fabric are all produced within the agreement countries. In other words, the rules of origin require a “triple transformation” to qualify for agreement benefits.

[7] In some cases, the necessary inputs are not produced (and therefore not available) within partner countries. In response, countries may agree to “exception levels” that allow for inputs produced in non-party countries to be included in products without losing agreement benefits.

[8] In well-established results, expanding the set of inputs in a constant elasticity of substitution (CES) production function increases output and generates growth. When inputs are differentiated, increasing the set of inputs can increase the demand for other inputs as firms expand.

[9] Apparel products are grouped into three broad categories natural (cotton and other natural fibers), synthetic, and blended fiber-based. See the concordance tables by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

[10] The impact of trade on employment and poverty reduction, UNCTAD: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/cid29_en.pdf

[11] Southwest Land Border Encounters (By Component), U.S. Customs and Border Protection: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-land-border-encounters-by-component

[12] Heterogeneous Trade Agreements and Adverse Implications of Restrictive Rules of Origin: Evidence from Apparel Trade, SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4376016

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).