Published 04 July 2023

International patenting flows have grown significantly as the global economy becomes more interconnected, but our understanding of their relationship remains inadequate. Drawing from a report published in the Canadian Journal of Economics, this article examines how cross-border patenting and trade have co-evolved over time, and the impact of patent protections on globalization.

During the past several decades, the world economy has undergone substantial globalization, resulting in significant growth in both international trade and international patenting flows. Although these trends are concurrent, our understanding of how they may be linked is limited.

In theory, the relationship between patenting and trade could be ambiguous, with patents potentially acting as either complements or substitutes for trade. For example, a firm looking to export microchips to a foreign market may file for a patent in that market to prevent the technology from being copied, leading to an increase in trade. Alternatively, a multinational firm might use a patent to establish its own production facility in a foreign country, thereby bypassing the need for trade. In some cases, patents may be filed to prevent foreign firms from producing competing goods, with no significant relationship between patenting and trade. It could be possible more broadly for trade and patents to be complements in some industries and substitutes in others.

Given these complexities, determining the existence and nature of the relationship between patenting and trade requires careful empirical investigation. We have drawn on an academic article we recently published in the Canadian Journal of Economics (Brunel and Zylkin, 2022) to provide an overview of how cross-border patenting and trade have co-evolved over time.

Growth of international patenting

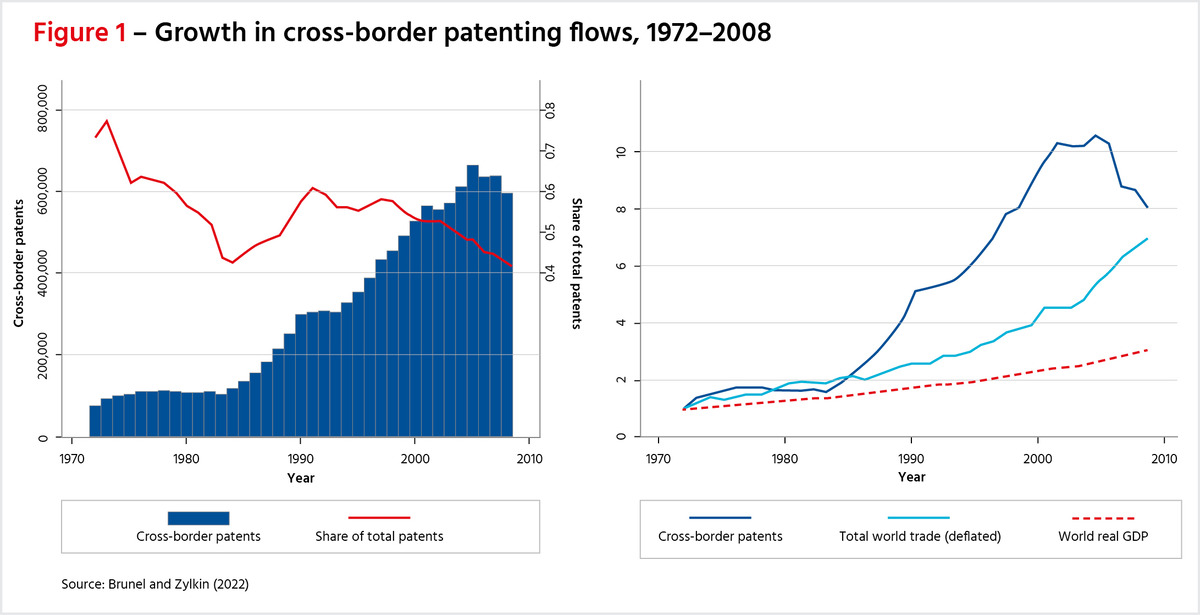

With technological advancements a key force behind economic growth and globalization, it is no surprise that patents, like global growth and global trade, have grown significantly during the last several decades. Cross-border patents—patents filed in one country by a resident of another— have increased significantly in the past few decades, growing faster than both world output and world trade during the period 1972-2008 (Figure 1b). From less than 100,000 in 1972, the number grew to 600,000 by 2008 (Figure 1a) and to one million by 2021 (WIPO 2022, p. 9). The driving force behind this surge in cross-border patenting is the overall growth in patenting: the share of cross-border patents in total patents has steadily declined due to an even larger increase in the number of patents filed by residents, especially in China (p. 9). While cross-border patents previously represented about 70% of total patents, this share fell to 40% by 2010 (Figure 1a) and just 30% in 2021 (p. 9).

Different countries are filing patents

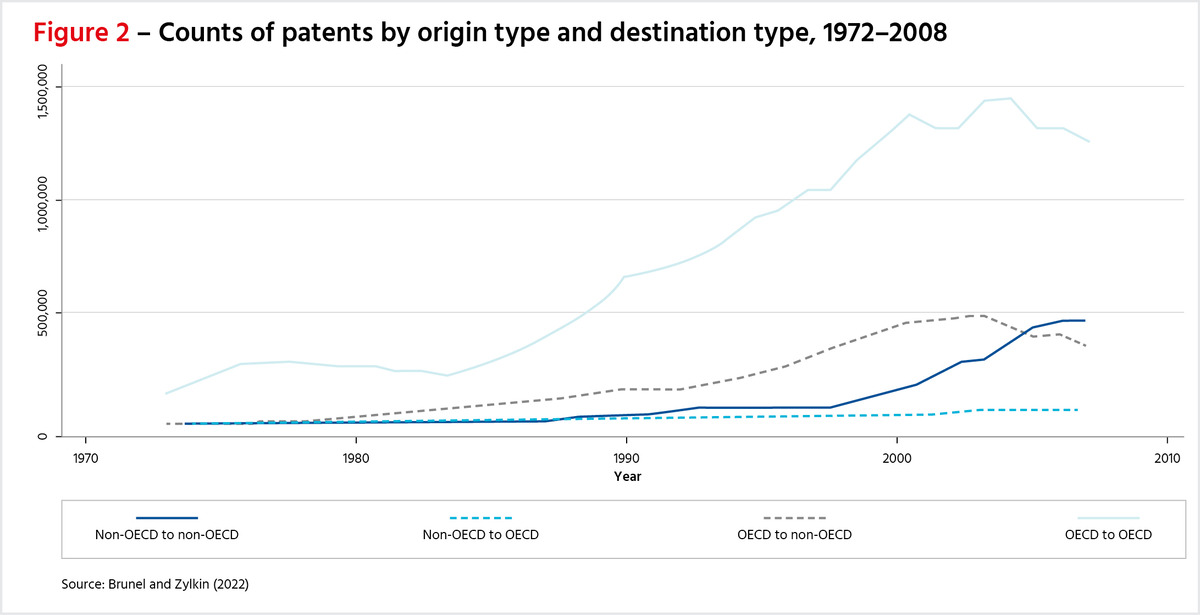

While cross-border patents have always been dominated by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) residents filing patents in other OECD countries, we see some interesting trends among other country groupings as well. Starting in the late 1970s, patent filings from OECD residents to non-OECD countries have grown significantly, from about zero to nearly 400,000. By the early 1990s, we also observe a large increase in filings by non-OECD residents into non-OECD countries. In fact, our analysis concludes that cross-border patents in non-OECD countries are mostly filed by residents of other non-OECD countries rather than by residents of the OECD.

These figures are based on a simple count of the number of patents filed and as such do not reflect how patents might differ in their value. Accounting for a measure of how valuable an innovation is, we find large growth in cross-border patent filings originating from Japanese residents. Portugal, China, Poland, and Greece have seen large growth in patent filings by non-residents in their countries. However, as mentioned above, patent filings in China, which have increased tremendously in the past few decades, are still dominated by applications from Chinese residents.

Broadly, these patterns are suggestive of other, simultaneous changes known to be happening with other markers of globalization, such as the similar changes that have taken place for flows of international trade and investment. Focusing on trade, our recently published research asks whether cross-border patenting has helped lay the groundwork for the growth of trade as opposed to responding to it or merely coinciding with it.

To answer whether cross-border patents promote trade, we overcome several challenges. For example, a patent for a pharmaceutical innovation filed in Germany may not be worth the same as a patent protecting a technology for textiles filed in Bangladesh. A computing technology from fifteen years ago may have lost much of its value as more recent innovations have rendered it obsolete. Using the most cutting-edge methods for studying international trade data, we analyze an extensive database of industry-level trade flows and patent filings for 249 disaggregated industries and 149 countries for 32 years from 1974 to 2006. Our findings suggest an overall complementary relationship between patents and trade: an increase in patents from Country X to Country Y tends to stimulate exports from Country X to Country Y as well, while we see no significant change in imports in the opposite direction. To give a sense of the magnitude, the difference between a “high value” flow of patents and a “low value” flow of patents is an average increase in exports of 8.87%. As a point of comparison, this is more than half of the average effect that a free trade agreement has on industry-level trade in our analysis.

We also observe some interesting industry-level heterogeneity, notably based on the level of differentiation in the industry. Footwear is a highly differentiated industry, as footwear products vary along many dimensions including type (sneakers versus high heels), materials (cloth versus leather), or color. Crude oil, on the other hand, only has a small amount of differentiation in the sense that a barrel of crude oil is essentially the same across suppliers, with some slight quality differences. Surprisingly, we do not find that patents have stronger effects on trade in more differentiated industries where we would expect monopoly rights over a product’s distinguishing characteristics to be more valuable. Instead, patents have larger effects in less differentiated industries, implying that patents are mostly used to preserve advantages in production costs and/or product quality against foreign competitors. Another interesting result is that patents are effective at securing these advantages regardless of the strength of the local intellectual property rights (IPR) regime. It does not appear that to affect trade, patents require strong enforcement of IPR.

Recent developments in cross-border patenting

Apart from a few industries, such as computer technology, the pandemic led to a general slowdown in patent filings. However, overall, filings are now back to pre-pandemic levels, and the recent growth in the top 20 patent offices can be attributed primarily to cross-border patents (p. 9). Members of the World Trade Organization have agreed to waive IP protections for Covid vaccines and are currently debating whether to similarly waive protections for Covid diagnostics and therapeutics. In another move that affects cross-border patents, WTO members agreed to extend the deadline for least-developed countries to protect intellectual property under the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) until July 1, 2034.

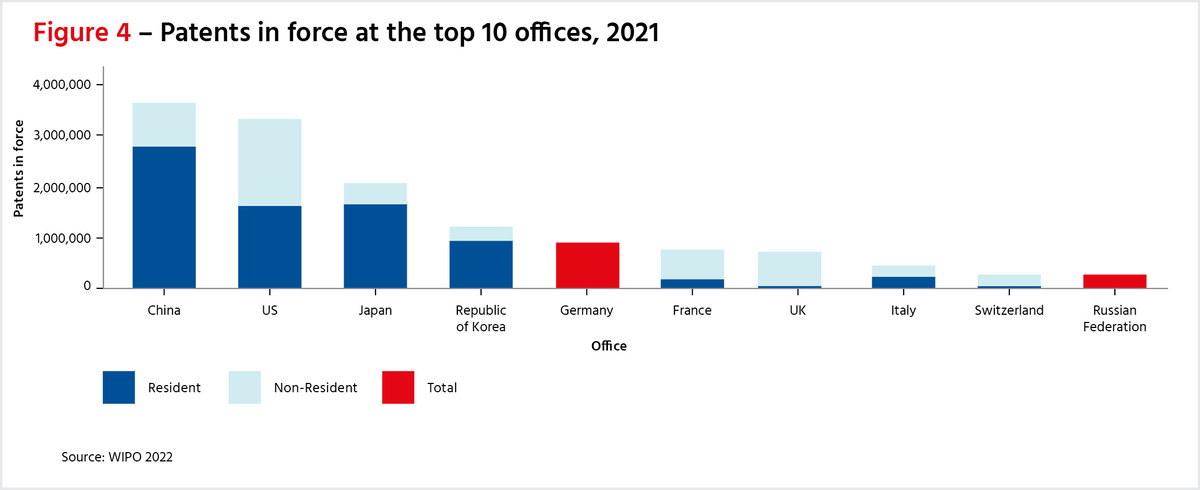

Looking at recent developments in cross-border patenting trends (p. 10), many of the most prominent patent offices have received large shares of non-resident filings: Australia, Canada, the European Patent Office, India, and the United States all receive at least half of their patents from non-residents. For other smaller patent offices such as Mexico, Brazil, Singapore, and Indonesia, more than 80% of the applications are for cross-border patents. China, on the other hand, received very few patent applications from non-residents—about 10%.

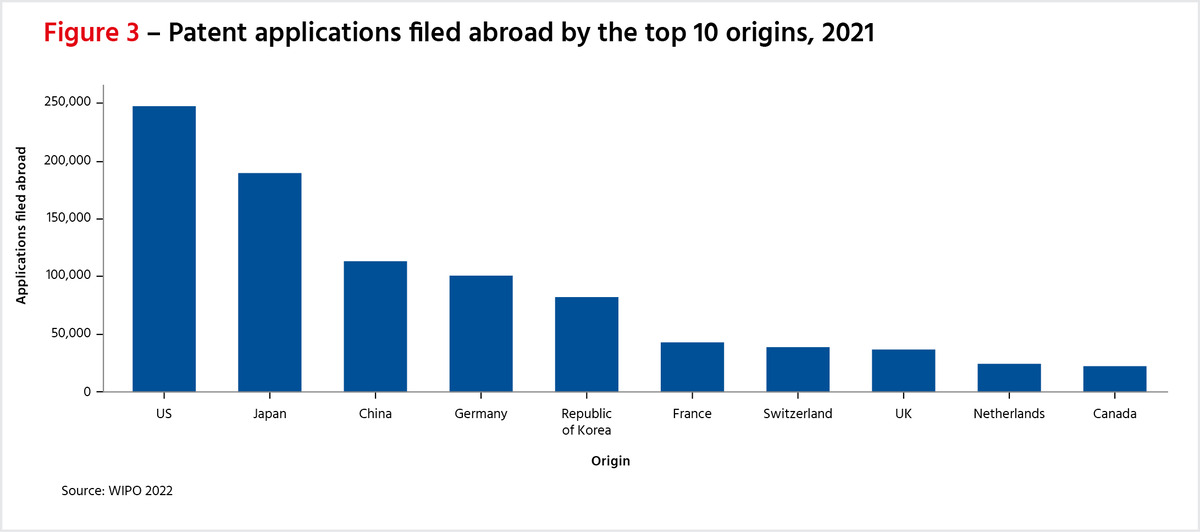

Examining the source of cross-border patents, residents of the United States, Japan, China, and Germany continue to dominate cross-border patent filings. In 2021, US residents filed nearly 250,000 patent applications abroad, more than twice the number of applications filed abroad by Chinese residents (Figure 3). However, considering both resident and non-resident patents, 2021 marked the year when China surpassed the US to become the top jurisdiction in terms of the number of patents in force (Figure 4).

Conclusion

As globalization continues to shape the world economy, the policy questions and economic activities connecting international patenting and trade remain active areas of research and debate. Our recent article in the Canadian Journal of Economics sheds light on these issues by bringing together cutting-edge methods from the study of international trade with industry-level data on patenting and trade flows. Overall, we found that patents have been historically useful for promoting trade. As the policy environment surrounding patenting and the nature of innovation continue to change over time, substantial future work can be done to better understand this relationship and provide guidance on the potential of patent protections to unlock and/or impede the path of globalization.

***

Brunel, C. and T. Zylkin (2022). “Do Cross-border Patents Promote Trade?”, Canadian Journal of Economics, 55(1), 379-418.

WIPO (2022) World Intellectual Property Indicators.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).