How to use it

Women and trade: How trade agreements can level the gender playing field

Published 12 September 2023

Unlocking women’s potential to participate in trade could expand economic growth significantly. Trade policy and trade agreements can play a role in creating a more equal and equitable playing field for women. This brief from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) explains the current landscape for women and the challenges they face, the role trade policy has played, and how trade policies and trade agreements can be drafted to achieve a more equitable future.

Here’s how to use the CSIS brief entitled Women and Trade: How Trade Agreements Can Level the Gender Playing Field.

Why is the women and trade brief important?

Governments increasingly consider steps they can take to advance gender equality – the absence of discrimination on the basis of gender – and gender equity – fair and just distribution of benefits and responsibilities between genders. The brief contributes to this work by offering specific recommendations and provisions that can be adopted to shape trade policy and trade agreements to further the goal of gender equity.

What’s in the Women and trade brief?

The brief includes the following four principal sections:

Introduction; The nexus of gender and trade

- According to McKinsey, women only contribute 37% to global GDP; removing obstacles to women’s economic participation could raise global GDP by US$12 trillion. (p. 2)

-

Gender is relevant to trade; countries that are more open to trade show higher levels of gender equality, but, women do not benefit from all practices encouraged by trade liberalization. (p. 3)

Women face higher export costs, higher rejection rates for trade finance, and tend to be employed in services sectors that face larger disruptions from trade; limited trade data is disaggregated by gender, hindering persuasive arguments for change. (pp. 3-5, Figures 1-3)

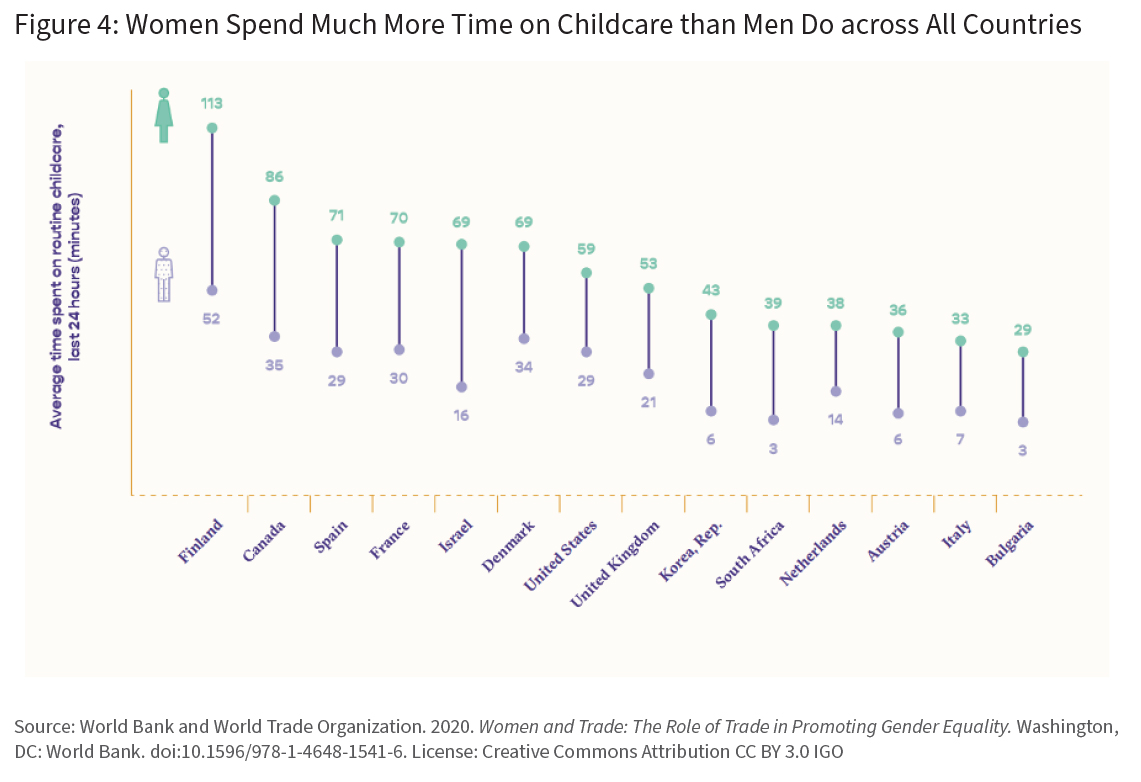

Key barriers to trade are 1) greater time constraints imposed on women compared to men due to burdens of unpaid domestic work, particularly childcare; 2) higher costs imposed on women exporting across borders; 3) concentration of women in services sectors not engaged in trade; and 4) unequal protection under law in 180 out of 190 countries. (pp. 7-8, Figure 4)

Roles of gender in trade agreements

-

Three ways to advance trade and gender work are 1) domestically implement trade policies to mitigate gender inequity; 2) World Trade Organization (WTO) Member collaboration to understand gender’s impact on trade and trade’s impact on gender equality; and 3) using trade agreements to act as levers for reform to advance women’s participation in trade. (pp. 9-10)

-

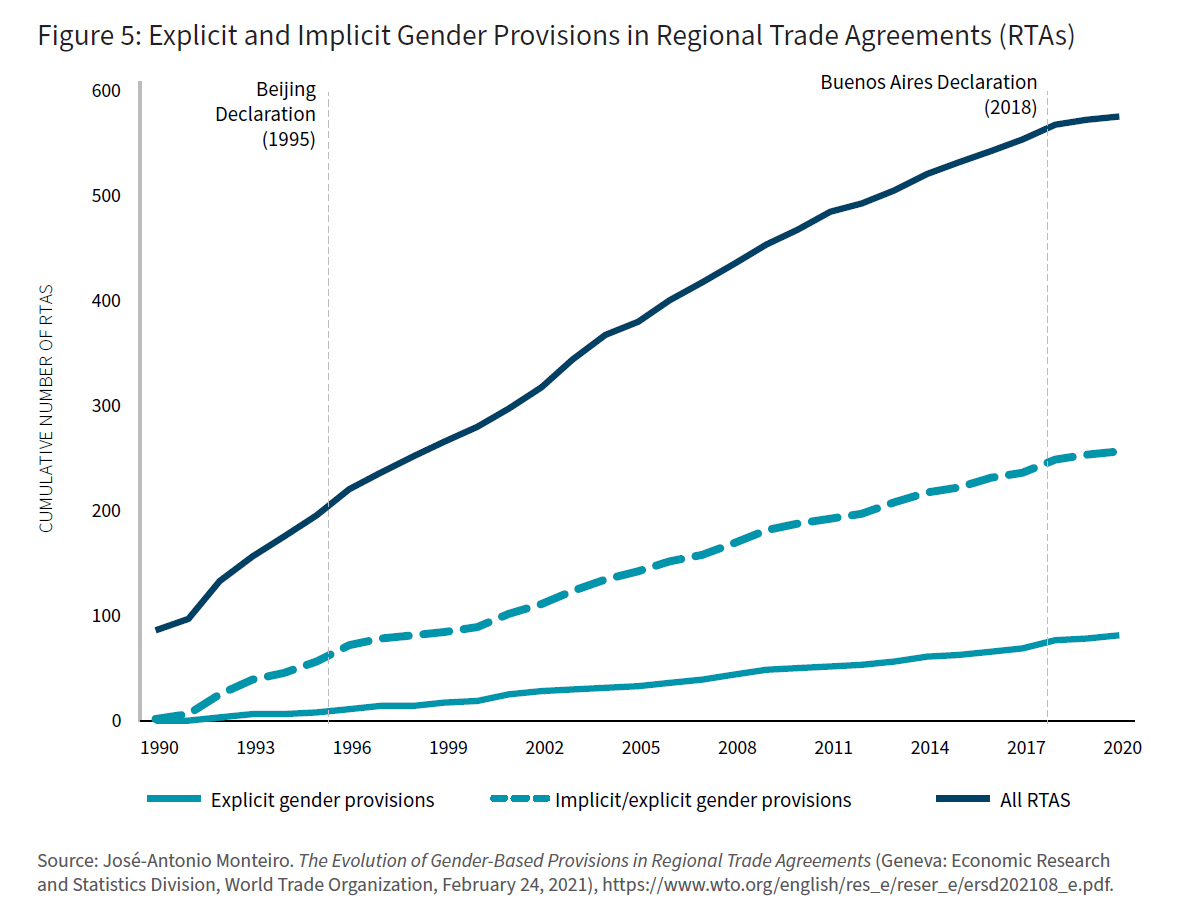

As of December 2020, only 27 percent of regional trade agreements explicitly referenced gender, through standalone trade and gender chapters, or by “mainstreaming” – including binding gender commitments throughout the agreement. (pp. 10-11, p. 17, Figures 5 and 10)

-

This paper assesses the gender responsiveness of trade agreements; whether and to what degree a trade agreement acknowledges and seeks to mitigate trade barriers to women; measurement of gender impact is ideal but not possible given the limited data available. (p. 12)

-

The Korea-US Free Trade Agreement has limited gender responsiveness as it does not make explicit reference to gender and has only limited implicit references. (pp. 12-13, Figure 7)

- The Canada-Israel Free Trade Agreement has advanced gender responsiveness, including specific gender provisions throughout the agreement and a standalone chapter on gender that is binding under the dispute settlement mechanism. (pp. 13-16, Figures 8-16)

The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement has evolving gender responsiveness (midway between limited and advanced), with gender-specific clauses in key provisions, including labor provisions subject to dispute settlement, but no standalone gender chapter and no specific measures to prevent gender-based discrimination. (pp. 16-18, Figure 9)

The draft WTO Electronic Commerce Agreement has limited gender responsiveness, with potentially no explicit references to gender and few implicit references despite market growth that could result from gender-equitable access to e-commerce. (pp. 18-19, Figure 11)

Trade negotiations

- In the US context, gender has been ignored in trade negotiations due to a lack of 1) social impetus until now, 2) political salience, and 3) gender diversity and representation in stakeholder consultations that inform trade negotiations. (pp. 20-21)

How to apply the insights

-

In order to remedy shortcomings in trade agreements, it is critically important to understand the reasons that underlie the lack of focus in the area and assess whether those reasons are relevant.

-

This section provides a brief but thoughtful summary of the reasons behind the absence of gender in trade negotiations for policymakers to consider.

Recommendations

-

In order to advance gender equity in trade, negotiators and policymakers can:

-

Include gender-specific language in trade agreements through mainstreaming and gender-specific chapters that are subject to dispute settlement; gender-responsive language should be included in the preamble and labor, services, dispute settlement, and other chapters; gender-specific chapters should be both binding (commit parties to address grievances) and compulsory (trigger a dispute settlement process). (pp. 22-29)

-

Prioritize gender in trade agreement negotiations by ensuring diversity and representation of women in trade advisory committees and the stakeholder engagement process; creating trade and gender advisory committees through transparent and inclusive processes; and committing to collect gender-disaggregated data to measure any disproportionate impact of trade agreement provisions. (pp. 29-20)

-

Prioritize gender in domestic policy to further trade goals, including by prohibiting all gender-based legal discrimination; applying a gender lens and gender-based analysis to trade policies and agreements, tariffs schedules, agricultural subsidies, public procurement, and partnerships with the private sector; and improving infrastructure (facilities essential for everyone to do their jobs) to reduce the impact of gendered barriers, including access to childcare, environmental protection and climate change mitigation, broadband internet access, and traditional infrastructure. (pp. 30-34)

-

-

The US specifically should join the WTO Informal Working Group on Trade and Gender, revise the US Trade Promotion Authority (which allows trade agreements to be “fast-tracked” through Congress without amendment) to prioritize gender equity as a negotiating objective, and include provisions from the Women’s Economic Empowerment in Trade Act in Generalized System of Preferences renewal. (pp. 35-36)

How to apply the insights

-

This section is exceptionally helpful for policymakers, legislators, and negotiators as it provides specific recommendations, including exact language and provisions to adopt for greater gender responsiveness in trade agreements.

Conclusion

The Women and Trade brief from CSIS provides a concise and persuasive argument for considering gender in trade policy and trade agreements, with highly specific recommendations and exact language to adopt for drafting more gender-responsive trade policies and agreements.

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- COVID recovery and the power of women exporters

- Aligning trade and human rights

- Sustainable Trade Index 2022

External Resources

- Trade and Gender: A Framework of Analysis – OECD

A proposal for a framework analyzing the impacts of trade and trade policies on women. - Why the gender gap in international trade needs to close faster – Ernst & Young

What can organizations do to benefit women’s development and economic growth? - GTAGA: The Global Trade and Gender Arrangement, decoded – International Institute for Sustainable Development

What can multilateral agreements do to enhance gender equality in trade?

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).