How to use it

Optimizing export controls for critical technologies

Published 07 November 2023

As the world becomes more geopolitically fragmented and technological development spurs Great Power competition economies worldwide are considering means to balance competitive advantage with national security, including by imposing export controls on critical and emerging technologies. This report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies dives into these issues.

Here’s how to use the report entitled Optimizing Export Controls for Critical and Emerging Technologies.

Why is the report important?

The report contributes to the policy debate over how the US should reform its export controls rules to address the new challenges posed by critical and emerging technologies by providing in-depth information on the benefits, risks, and nature of four key critical and emerging technologies: Semiconductors, quantum technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and biotechnology. It offers suggestions on how to approach reforms. This report makes the critical point about the need to find the right balance between encouraging innovation, exploiting commercial applications of new technologies, and protecting national security. It also makes obvious the need for clear rules and definitions, and clarity of purpose underlying export controls.

What’s in the report?

It includes three principal sections:

Introduction and national security

- The US strategic technology framework faces challenges from multiple adversaries in both the security and economic realms; the importance of maintaining US technological superiority and responding to China’s ambitions underscores the need to envision a new strategic technology framework. (p. 1)

- The post-World War II export control structure to prevent the Soviet Union from acquiring critical dual-use technologies was an export-licensing system requiring allied permission to export sensitive items, most of which were physical products. (p. 2)

- After the fall of the Soviet Union, the US transitioned to an export control system based on end-user analysis, requiring a determination of bona fide end-users with conditional licenses that only allow specified users in specified activities to use the item. (p. 2)

- Two policy elements have been difficult to reconcile: ensuring military capabilities and national security versus maintaining an economic advantage; the US needs to define what merits control more clearly and what does not. (p. 2)

- Defining what merits control requires determining what technologies are critical to national security, and what “national security” encompasses. (p. 5)

- National security was first defined as activities related to foreign relations and protection from internal subversion, foreign aggression, and terrorism, and later control of nuclear technologies or non-proliferation. (p. 5)

- Recently there has been a push to approach national security from a wider perspective, connecting domestic economic prosperity and national security interests. (pp. 5-6)

- Existing export and technology control lists (Wassenaar Arrangement, Commerce Control List, Critical and Emerging Technologies, CFIUS Guidance, and Outbound Investment Reviews) do not agree on what is important to national security; each list serves a distinct purpose, giving the government greater agility to control exports, but confusing the private sector; assessing where the lists overlap can shed light on national security definitions and provide guidelines for future reform. (pp. 6-11)

- Based on the Biden administration's public statements, quantum technology, AI, semiconductors, and biotechnology are national security priority areas. (p. 11)

Critical technologies

- As economic security is increasingly conflated with national security, the US government must clearly define its strategic objectives to avoid the appearance of protectionism and ensure that controls on advanced technologies are surgical and narrowly targeted to avoid depriving firms of export-based revenue. (p. 12)

- Determining criticality depends on dividing technology into specific categories based on specific applications; hardware, software, and other intangible items like knowledge transfer (deemed exports) can all be critical to national security interests, with enforcement of controls of deemed exports representing an inherent challenge. (pp. 12-13)

- Quantum technologies can be divided into three subcategories: sensing, computing, and communications; of these, sensing is currently poised for mission use while computing and communications are still emerging. (pp. 13-14)

- Quantum technologies can be divided into three subcategories: sensing, computing, and communications; of these, sensing is currently poised for mission use while computing and communications are still emerging. (pp. 13-14)

- There is a debate over how to implement export controls of quantum technologies; the industry focuses on qubits, though other thresholds may have value; physical components and proprietary software may also be good bases for controls. (p. 16)

- Challenges to placing export controls on quantum technologies include:

- the need to focus controls narrowly to avoid putting US industries at a competitive disadvantage and restricting access to the large ecosystem needed to develop technology and explore commercial opportunities;

- determining what metrics to use when identifying thresholds for controls;

- the multiple ways that quantum computers can be built and that different methods require their own inputs; and

- the absence of horizontal integration which makes production more expensive now and export controls even more costly. (pp. 16-18)

- Instead of controls, the US government should focus on increasing domestic quantum technology capacity. (p. 18)

- Semiconductors are both one of the most critical national security technologies and a key part of the civilian economy with highly complex global value chains with many potential chokepoints requiring high levels of international coordination to enforce export controls effectively; the US and Taiwan represent the world’s strongest chokepoints for the most advanced chips. (pp. 18-19)

- Chinese military AI systems use US chips, allowing US export controls to degrade Chinese AI capabilities; the US adopted unilateral export controls on advanced AI chips to China, later coordinating with Japanese and Dutch governments; the new controls end the licensing policy based on identifying reliable end-users; the CHIPS and Science Act also sets our guardrails restricting funds from bolstering enterprises that could pose a national security risk. (pp. 19-21)

- Concerns with current and future semiconductor export controls include:

- the economic health of the semiconductor industry and consequently its ability to withstand the costs of additional controls;

- China’s potential retaliation by weaponizing trade in mid-tier chips which could further depress revenue and cause firms to reduce R&D funding and undermine innovation;

- the availability of technological workarounds using less advanced equipment that undermine the effectiveness of controls;

- the disproportionate economic effects of additional controls because of insufficient supply of memory chips in the US and location of supply chains in China;

- whether China and other countries will develop their own products, “designing out” US technology and allowing their own companies to capture their domestic market share;

- whether US companies can find alternative markets to make up for the loss of China as a customer; and

- porousness of controls enforcement. (pp. 21-23)

- Long-term costs of the US controls on semiconductors may be larger than expected and become a drag on the US industry’s ability to compete and inspire other entrants into the market; the best approach is to maintain current controls but treat them as a moving target while making clear that controls apply to all end users and uses in China through a policy of denial of license applications. (p. 23)

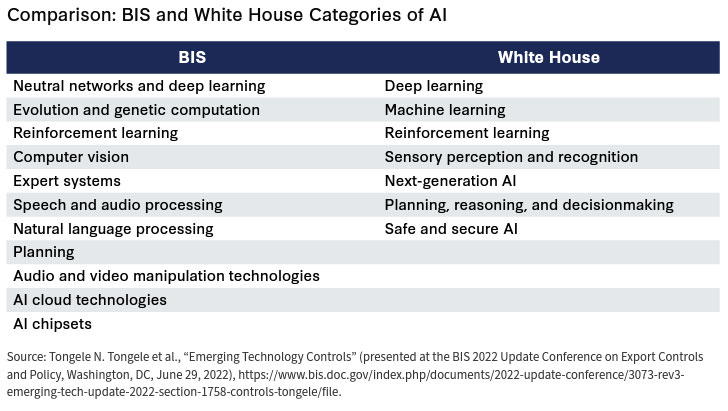

- Artificial Intelligence is generally considered to be computer systems that simulate human-level cognition; the AI supply chain relies on gathering raw data to train AI models; in the modeling phase of development, export controls would apply to data used to train AI models; AI can be categorized as narrow, general purpose, superintelligence, or generative, with narrative and generative currently operational while general and superintelligence AI do not yet exist; all forms could pose threats to national security. (pp. 23-24)

- There are few operational definitions of AI in the context of supply chains; October 7 export controls on AI capabilities have focused on hardware components though there is an urgent need to develop controls for intangible goods like algorithms; given the intricacies of controlling this technology, developing uniquely tailored controls is critical; the US should consider building new export control rules for dual-use data flows that feed AI systems. (pp. 24-25)

- Biotechnology is important as a force multiplier throughout the tech ecosystem and an important sector for economic growth; the US has deemed leadership in biotechnology as a national security imperative; the US has taken steps to remediate risks of relying on China for biotechnology and increase US investment; biotechnology has been designated as an emerging technology for export controls purposes; controls face the challenge of being strict enough to protect national security but flexible enough to facilitate economic growth. (pp. 25-26)

- Concerns over biotechnology include that it could potentially lead to the proliferation of bio-weaponry, or that applications could give bad actors access to DNA or personal health records; designing effective export controls is a complex endeavor as some applications have both significant benefits for civilians and potential for military applications; development and use of biotechnology are restrained by two chokepoints: reliance on people with know-how to develop innovations and access to data necessary to apply biotechnology innovations. (pp. 26-27)

- The US should work within the Australia Group to multilateralize controls on bioweapons; expand controls on data and knowledge transfers; and require exporters of personal sensitive biological data to obtain an export license for data flows with national security implications, allowing exemptions for healthcare data to move freely across borders in cases when the health security of the US population is imperiled by pathogens or other risks. (pp. 27-28)

- Intangible goods can include data, digital files, software, spyware, and machine learning models; weaponization of data may characterize conflict in the coming century; export controls of intangible goods will likely need to cover the data feeding these applications. (pp. 28-30)

- The US should create a new category under the Commerce Control List for intangibles, allowing the US to define data as an input and designate certain bulk data flows as inputs to certain end users and end uses harmful to US interests, allowing the US to require export licenses; the licensing process should create a new presumption of denial rule where the user has not explicitly consented to the export of their data; this approach shifts the US from its traditional free trade policies on data flows but represents a viable middle ground; a key remaining question will be where to set the thresholds for how many users constitute “bulk data”. (pp. 30-31)

Recommendations and conclusion

- If implemented correctly, export controls can both restrict the outflow of technology to foreign adversaries and advance industry interests that ultimately bolster US tech leadership. (p. 32)

- The report recommends that the US:

- Help domestic industry and allied economies “run faster’ in the race by ensuring that government support is consistent, sufficient, and iterative; this can include loosening immigration restrictions, providing financial incentives, and ensuring sufficient funding. (pp. 32-33)

- Create a new category governing data export; clearly designate data as a commodity, treat it as an input, and require exporters of certain data categories to seek an export license. (p. 33)

- Keep controls relatively light or flexible for emerging technologies, particularly quantum, as over-controlling industries can depress growth and innovation. (p. 33)

- Increase knowledge base by institutionalizing communications with the private sector to help educate the government about industry concerns and new technology developments. (p. 33)

- Increase funding for BIS and ensure that it remains part of the Department of Commerce. (pp. 33-34)

How to apply the insights

-

The recommendations section provides concrete actions that policymakers and lawmakers can take to develop appropriate new export controls regimes to apply to critical technologies, striking a balance between protection and allowing for innovation and economic growth, while the conclusion provides a clear and concise overview of the key lessons from the report.

Conclusion

The Optimizing Export Controls for Critical and Emerging Technologies report brings needed focus and important information to an important policy debate over control and regulation of technologies that will be critical to economic growth and innovation but also have the potential to compromise national security.

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- AI arms race shakes tech, trade, and truth

- Chipping away at global semiconductor supply chains

- Will US semiconductor restrictions on China backfire?

External Resources

-

Insight into the U.S. Semiconductor Export Controls Update – Center for Strategic and International Studies

How do 2023 export controls compare to the ground-breaking export controls issues in 2022? -

Biden Turns a Few More Screws on China’s Chip Industry – Foreign Policy

The US chooses to wield “a scalpel over a sledgehammer” in issuing additional export controls -

Commerce Imposes Significant New Controls on Advanced Semiconductors – Akin Export Controls and Economic Sanctions Practice Group

The legal details of new US export controls on advanced chips.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).