Published 16 June 2020

COVID-19 is likely to be looked upon as a watershed in the globalization process. The pandemic will act as an accelerant and catalyst for far-reaching changes in the global economy, some of which may have a lasting impact on trade. This article looks at four possible trade trends which could improve the quality and resilience of the world economic system.

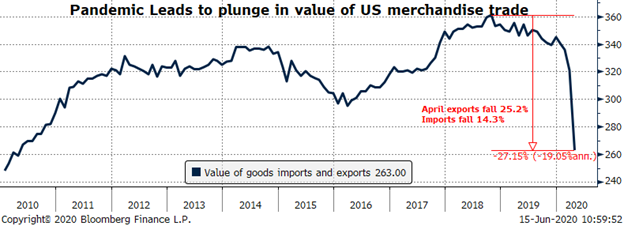

The Government-imposed “lock-downs” aimed at preventing the spread of the COVID-19 virus have brought the world economy to a sudden stop. This has resulted in a sharp cyclical contraction in dollar value and volume of trade, due to a cyclical collapse in demand (particularly for energy) and to price deflation. The result will be the sharpest and deepest contraction in trade and GDP since at least the 1930s.

The robustness and trajectory of the economic recovery is uncertain. In each of the past three global recessions, the amount of stimulus required to restart the economy has risen, the range of tools necessary to make monetary policy work has expanded, growth post-recovery has looked more anemic, and the growth benefits have seemed less evenly spread.

The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to accelerate and catalyze far-reaching changes in the global economy, some of which may have a lasting impact on trade and economic growth. This article looks at four structural trends which might be accelerated by the pandemic, and how they might impact the nature, quantum and speed of the global economic recovery:

1. Decarbonization

The “green agenda” was already gathering momentum. The pandemic has emphasized the impact of humans on nature and how threats to biodiversity and climate make use more vulnerable to diseases. The fiscal stimulus being implemented to restart the global economy should hopefully contain a larger green element that may help accelerate the decarbonization of our economies.

2. Decoupling

Before the pandemic, the asymmetric nature of the trade and investment relationship between China and most of its trading partners and China’s policy of “national rejuvenation” drove the acceleration of bilateral trade tensions between China and its partners.

COVID-19 will likely quicken and deepen the bifurcation of global value chains. Dependencies on China will be reduced, global value chains will be shortened, supply redundancy will become more common (and potentially more costly) and we may see more localization of production.

3. Automation

The de-Sinification of manufacturing, together with the pandemic-induced desire to reduce human interaction will likely accelerate advances in robotics and automation that were already underway. The productivity-enhancing benefits of this shift should be welcomed.

4. Usage of AI, big-data and digital currencies

Technology was broadly used to contain the spread of the virus. This has highlighted both the positive impacts of technology and its risks to individual liberty when misused. The pandemic may well have brought forward the widespread use of Artificial Intelligence and “Big Data”. This will include use of digital currencies which have the potential, among other things, to transform payment systems.

De-carbonization may reduce the volume of trade and trade imbalances, but not necessarily at the cost of dynamic efficiency

There has been a concerted move, particularly in Europe, to combine fiscal stimulus with a transition towards a low carbon or carbon-neutral economy. One potential consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, therefore, could be a more rapid decarbonization of the economy.

A total decarbonization is highly unlikely but there will be a trend to replace hydrocarbons as energy sources.

Trade in hydrocarbons and their derivatives currently account for about 12% of global trade.

Trade in hydrocarbons and their derivatives currently account for about 12% of global trade.

Trade in hydrocarbons account for about USD1.1 trillion or 6% of the total trade in goods. When you add the trade in hydrocarbon derivatives such as petrochemicals and refined products, the proportion rises to about 12% of global trade.

Total decarbonization is highly unlikely in the next decade., but the trend to replace hydrocarbons in energy will obviously put extreme downward pressure on this segment.

Energy is likely to be produced, on average, closer to market

Energy is likely to be produced, on average, closer to market. The comparative advantage will be determined by technology and the opportunity cost of alternative uses of resources such as land in the case of wind farms or solar farms.

If we ignore the externalities of carbon emissions, the economic cost of decarbonization will come not from the loss of trade per se, but from the higher resource intensity (and hence cost) of alternative energy sources, at least in the initial stages. Cost parity with hydrocarbons is a moving target as the collapse in oil prices this year demonstrates.

Locally produced energy will be far less widely traded internationally

Trade imbalances have contributed to discontent with the WTO system and unsustainable trade. Over the past twenty years, the global trade system has become increasing bifurcated between those countries that run continuous current account surpluses and those that have been running continuous deficits. This has led to accusations of malfeasance and called into question how trade adjustment mechanisms work.

Some of the biggest imbalances in trade have come from trading hydrocarbons and they will likely diminish substantially.

The hydrocarbon rich countries have been among the largest perennial current account surplus countries because the windfall created by hydrocarbon revenues has been recycled through capital accounts rather than spent on imports. The four big hydrocarbon economies of Norway, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait alone have run a cumulative current account surplus of over USD2 trillion in the past decade.

The decline of hydrocarbons in the energy mix is therefore likely to lead to more balanced global trade (meaning fewer examples of outsized surpluses and deficits), the corollary of which is less cross-border investment. Some sovereign wealth funds associated with hydrocarbons could well be depleted and with oil prices at current levels this could happen relatively fast.

While some countries are likely to have a comparative advantage in the supply of alternative or renewable energy, the advantage is likely to be far less significant than with hydrocarbons.

Decoupling and the de-Sinification of global value chains will change trade patterns substantially and improve resilience, but not necessarily result in onshoring

The desire to diversify global manufacturing away from China was already appearing.

Well before COVID-19 and the election of President Donald Trump, China’s rise to dominance in global manufacturing, which began in earnest with its accession to the WTO in 2001, was causing concern. The trade war initiated by the US in 2018 heightened tensions in the global trading system. The COVID-19 pandemic and China’s diplomatic offensive aimed at promoting its tight handling of the pandemic have further aggravated tensions.

The COVID-19 induced supply chain breakdown has highlighted a lack of resilience

Over the last 20 years, efficiency and therefore short-term profitability considerations have been prioritized over economic robustness and resilience. The pandemic highlighted the degree to which China had gained monopolistic power over particular segments of the supply chain.

Supply chain interdependence can severely limit the scope for independence of action at the national level.

Supply chain interdependence can severely limit the scope for independence of action at the national level. For some countries, of course, this is the whole point of globalization. For others, this means an inability to stand up to an expansionist power, protect their national interest and preserve a cherished value system without incurring large economic costs.

The need to decouple from dependent trade relationships – notably with China – has become an urgent policy driver for most nations.

China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy reveal the depth of dependency risks

China’s recent policy mix of military assertiveness, “wolf warrior” diplomacy and targeted medical aid revealed the extent to which it was willing to use its monopolistic power in global value chains for geo-economic goals and to inflict severe economic damage on other economies.

This has back-fired and achieved what many observers thought was impossible – driving world opinion towards, if not entirely in line with, the stance taken by President Trump.

Long-existing aspects of China’s political economy such as its Made in China 2025 industrial plan or the use of forced labor have suddenly risen in importance when they were previously over-looked.

The Chinese economy is more vulnerable to a relocation of industry than many think

In 2018, China’s manufacturing value-added totaled USD4 trillion or 29% of its GDP. This gave China a 28% share of global manufacturing value-added according to the World Bank, up from a mere 6% global market share at the time of its accession to the WTO. Furthermore, according to the ILO estimates, about 28% of China’s total employment is in manufacturing.

About 44% of China’s manufacturing is exported and about 13% of total Chinese employment is directly linked to exports. The implications of a de-Sinification of global value chains, even at the margin, are potentially dire.

With USD2.5 trillion of exports and a 30% import content to those exports, the implication is that about 44% of China’s manufacturing is exported. This suggests that about 13% of total Chinese employment is directly linked to exports. The implications of a de-Sinification of global supply chains, even at the margin, are potentially dire.

The cost to the US of rolling back economic engagement with China is not high

In contrast, US exports to China are less than 1% of GDP, the share of employment associated with them is even lower, and the profits made by US companies producing and selling within China account for less than 2% of overall US corporate profitability (although they are highly concentrated in a few firms).

In contrast, US exports to China are less than 1% of GDP, and profits made by US companies in China are less than 2% of overall US corporate profitability.

Evidence from the early stages of the tariff war suggests that about two-thirds of the loss in trade was made up for by a trade diversion away from China to the “second best” producer with little loss of welfare to the US consumer.

The aim is to reduce China’s political leverage and improve the robustness of supply chains

Reducing the reliance of supply chains from China will not be cost-free, and it will not happen overnight but the trend appears to be established.

Similar to the carbon centric economic model, the China-centric manufacturing model comes with externalities: namely, the enormous political leverage that China has gained through its ability to implement geo-economic policy that coerces countries to comply with, or at least not oppose, its geo-political agenda.

If an element of de-Sinification improves the robustness of supply chains, the short-term costs may prove worthwhile.

CPTPP becomes a valuable framework if industrial production starts moving away from China

The recently signed Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) provides a legal and operational framework for a China-free trade zone operating within the Pacific. Many of the likely shorter-term winners from a relocation of China-based manufacturing fall within this framework. CPTPP countries have a combined GDP as large as China’s and include many countries with substantial manufacturing capabilities.

The re-adjustment and relocation of supply chains takes time, and the logistical issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will make the adjustments more complicated and expensive in the short run.

But with little indication that the risks of manufacturing in China will diminish, nor any expectation that the rewards will increase, the incentives exist to de-couple and the trend will likely accelerate.

Advances in robotics and automation will help drive onshoring and improve productivity

Technological advances in transportation have often been associated with exponential growth in trade. Earlier episodes of rapid globalization were associated with canals, the transition from sail to steam shipping and containerization. This time, technological advances in manufacturing – robotics – could be a driver of onshoring.

One of the key drivers of global trade, perhaps accounting for up to one-third of growth in the past 20 years has been the labor-wage arbitrage. With advances in robotics, the labor cost component of manufacturing is now declining.

One of the key drivers of global trade, perhaps accounting for up to one-third of growth in the past 20 years has been the labor-wage arbitrage. This trend has had a debilitating impact on investment and hence productivity growth in high-cost economies, as off-shoring has been considered a more profitable alternative to productivity-enhancing investment in domestic manufacturing.

The automation of manufacturing processes and advancements in robotics mean that the labor cost component of manufacturing is now declining. For some industries this is well advanced already but as robotics become cheaper, the breadth of application will widen, and the barriers posed to onshoring by high labor costs and standards will be reduced.

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has induced a desire to reduce human interaction, will likely accelerate advances in robotics and automation that were already underway.

Digital currencies could make payment systems more efficient but equally result in further pressures on the multilateral system

COVID-19 has led to the wider adoption of technologies. China is trialing a digital central bank currency and other countries have expressed an interest in doing the same.

Efficiency in payments is one driver of this trend. The ability to bypass the SWIFT system and therefore reduce the efficiency of economic sanctions is another.

Whatever the motives, from a trade perspective two things are clear: a proliferation of digital currencies may accelerate the bifurcation of the world and hence could result in reduced multilateral cooperation. It could also significantly reduce dependency on the US dollar in trade transactions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is likely to be both an accelerant and catalyst for far-reaching changes in the global economy, many of which may have a lasting impact on trade.

Beyond the disastrous cyclical consequences of the pandemic, it might induce long-term changes that in a few years will have improved the quality and resilience of the world economic system.

Some may reduce the volume of trade, such as decarbonization, but not necessarily at the cost of a loss in dynamic efficiency.

Decoupling and the de-Sinification of global value chains may well change trade patterns substantially but not necessarily result in onshoring.

Robotics and automation could result in greater on-shoring but also improve productivity.

Digitalization of central bank fiat currencies could make payment systems more efficient but equally could result in a further pressure on the multilateral system.

Whichever outcomes prevail, COVID-19 is likely to be looked upon as a watershed in the globalization process.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).