Trade distortion and protectionism

Rising copper prices: a sign of economic recovery or market distortion?

Published 06 July 2021

Historically, demand for copper – a metal used to fill our everyday needs – is a sign of economic health. Is the recent spike in copper prices a sign of post-pandemic recovery or a market distortion caused by China's stockpiling? Critical to global plans for a low-carbon future, will the fight for copper supply lead to “resource nationalism”?

Why are copper prices so high?

When copper prices rose above US$9,000 per ton in February this year for the first time since September 2011, market watchers took notice. Analysts are speculating about whether the price spike is temporary or whether copper is in a commodity supercycle and set to trade at high prices over a long period. A new and critical question is whether China’s buying spree is the main cause of historically high prices. With demand forecast to grow globally and China vacuuming up copper resources, will copper reserves run short?

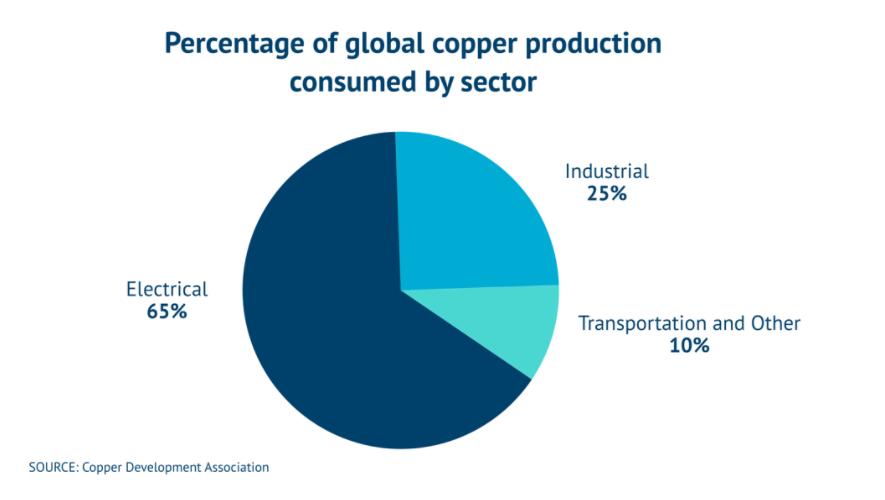

Copper demand is an historically reliable indicator of economic health. It is a “workhorse metal” used across industries and consumer applications, from plumbing and refrigeration to smart phones and solar panels. Given its ubiquity, copper demand rises when factories expand, more homes built, and cars produced. So, is the steep rise in the price of copper a sign of post-pandemic recovery, or a market distortion caused by China’s stockpiling when demand – and prices – were low during the pandemic?

Copper is critical to a low-carbon future

Copper is an efficient electrical and thermal conductor, easy to alloy and twist into wires. It has anti-microbial properties ideal for use in medical products such as surgical robots, implants, and MRI scanning machines. In addition to its myriad uses, copper will play an integral role in the 21st century low-carbon economy, which is underpinning predictions for significant new demand.

Because copper is incorporated into renewable energy generation including solar, wind, and geothermal, the World Bank estimates that clean energy alone will push global copper demand to rise by 200 percent by 2050. (1) That figure does not yet include copper usage for energy storage or for upgrading transportation systems and building construction.

Copper is also critical for water and sanitation infrastructure, including pump motors, electrical wiring, heat exchangers, and other electrical equipment used to treat wastewater. Looming water scarcity caused by industrial demand and climate change is expected to prompt a doubling of global investments in wastewater reduction, water remediation, and desalination over the next decade.

Electric vehicles (EVs) are also driving demand. Although EVs today comprise a small percentage of the global car market, in two decades their share could grow to 80 percent of global car sales.(2) Whereas the average gas engine vehicle now uses 20 kg of copper, the average hybrid vehicle uses 40 kg. Plug-in EVs use an astonishing 109 kg of copper.

The trends inducing higher copper demand are global. The G20’s Global Infrastructure Outlook estimates that US$94 trillion in investment is needed across 50 countries to meet the Sustainable Development Goals by 2040. (3) Some US$236 billion would be needed each year until 2030 just to meet the water and electricity goals. In the US, President Biden’s infrastructure plan alone outlines US$1 trillion in spending that could necessitate use of another 110,000 tons of copper annually.

China is storing up

Although copper prices are strongly correlated with world trade and with regional GDP growth in China, the United States, and the European Union (4), China is the world’s biggest buyer. China currently consumes more than half of the world’s refined copper. Copper prices are thus intertwined with the Chinese economy, and in particular the Li Keqiang Index that tracks China’s industrial growth.

Before COVID-19, copper sold at around US$5,800 per ton. Today, copper is widely expected to remain above US$8,500 a ton for some time.

In part, blame execution of China’s Made in China 2025 strategy, which calls for copper usage to grow by an additional 232,000 tons. The country’s increasing shift to renewable energy also drives demand, as does its ambition to be a leading electric vehicle manufacturing center by 2025.

To accommodate these industrial goals, China’s State Food and Strategic Reserves Bureau embarked on a copper buying spree when the price fell during the economic downturn in 2020. An already tight global copper supply grew tighter. The Reserves Bureau will not disclose the volume of its purchases. But China’s net imports of refined copper surged by 38 percent to 4.4 million tons in 2020 – 1.2 million tons more than in 2019.(5) According to the International Copper Study Group, that is equivalent to a 600,000-ton statistical supply-demand deficit. (6)

Enough copper for the future?

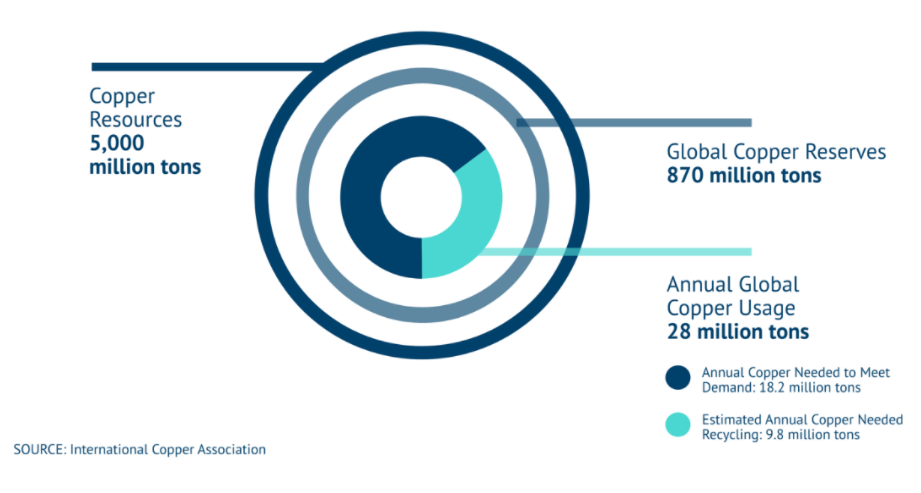

Long-term demand projections based on an increasingly copper-intensive global economy have prompted concerns about whether production can keep up.

To date, about 700 million metric tons of copper have been mined. According to estimates from the US Geological Survey, some 2.1 billion metric tons of discovered copper resources remain, mainly in Chile, Australia, Peru, the United States and Mexico. (7) Potentially, another 3.5 billion metric tons are yet to be unearthed. But the copper must be extracted. While mining production more than doubled between 1995 and 2019, the Copper Alliance projects actual production will only increase by 50 percent in the next 20 years. (8)

Even if the necessary investments are made to expand production, some industry analysts predict a shortfall exceeding 4.7 million metric tons in the next decade. (9) This vast shortfall rises to 10 million tons if mines are not built or expanded.

The perceived supply deficit prompts another question: Will it lead to “resource nationalism,” as when China threatened to restrict exports of rare earths to the world?

The answer is not yet clear. Produced in more than 20 countries, copper extraction is not reliant on one dominant country. Financial analysts believe this geographic dispersion of reserves and production reduces the possibility of tensions in global trade.

Green metal, green dilemma

The tensions between the benefits made possible by copper – widespread electrification and renewal energy generation – must be weighed against the environmental costs of mining the metal. Unearthed copper deposits are often located in places that are challenging to access, may be ecologically sensitive, or unregulated and controversial to mine – sometimes, all three.

Even though copper has burnished its decarbonization credentials, the mining industry often faces public opposition. Companies are often embroiled in lengthy legal and political battles to secure regulatory approvals to develop or expand underground mines. Increasing production outside China is not nimble, due to the complexity, cost, and uncertainty of regulatory approvals in other jurisdictions. The average lead time from discovery to production has extended from four to almost 14 years. (10)

Consider these examples of protracted exploration. In the United States, the proposed Resolution Copper mine in Arizona could supply up to one-quarter of the country’s copper demand. The company has argued that a steady domestic copper supply extends US manufacturers a competitive advantage. Yet the project has been slowed by stakeholder opposition.

In Peru, the La Granja are in the northern highlands has been targeted by Rio Tinto for development. But its 9,000 inhabitants have expressed concerned about emissions, intensive water use in operations, and the possibility of arsenic leaching into the water supply.

In the southern Philippines, a mining consortium is proposing to develop the Tampakan copper mine, estimated to hold 15 million tons of copper. When the provincial government imposed an outright ban on open-pit mining operations, the project was suspended.

Copper can be recycled indefinitely without performance loss. Yet increasing recycling offers only a partial answer because demand is so high. Even 100 percent of copper recycling would meet just 25 percent of global demand. To move ahead with more certainty and alacrity in expanding copper production, the global industry is working to integrate renewable energy into mining operations and production to mitigate emissions and address environment concerns.

China is not waiting, however. It is investing wherever it can, and it is moving quickly.

Resource nationalism

When China restricted global exports of rare earths, the United States and other governments took the country to dispute settlement in the WTO and won. That should have been a wake-up call to China’s efforts to secure its supply of inputs critical to industrial production and national security.

In a sluggish response, the US Government undertook “A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals,” initiated by the Trump administration in 2017. The US Department of the Interior identified 35 critical minerals that are both high national importance and at risk of supply disruption. Fourteen of the 35 minerals are not produced in the United States at all. The US imports only about one third of copper metal supplies, so it did not make the list.

The copper industry has criticized copper’s omission from the list as short-sightedness. Not only is copper used increasingly in critical infrastructure, but several elements on the list are produced as a byproduct of copper mining.

China has taken a different approach. Producing only eight percent of global copper, China imports 80 percent of its copper needs. It comes as no surprise, then, that Chinese state-owned enterprises have been dispatched to hedge the country’s supply bets by acquiring mines and equity stakes in overseas mining companies. According to S&P Global, China is engaged in 52 primary copper projects in Africa and Europe.(11)

After the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in 2014 simplified approval procedures for foreign transactions,(12) private Chinese companies stepped up their copper investments too. As Chile and Peru account for around 55 percent of China’s copper imports, South American mining ventures are an attractive target. In response, the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee is tracking China’s moves in the region’s extractive sector. (13) It has cited recent deals such as the US$1.4 billion Mirador mining project in Ecuador and a US$1.3 billion expansion of the Toromocho copper mine in central Peru as sources of national security concern.

Investments in Africa are also increasing. According to S&P Global, while the combined overseas exploration budgets of Chinese companies fell from US$267 million in 2011 to US$101 million in 2020, (14) most of the decline occurred in Canada, Southeast Asia, and Australia, which dropped from 22.5 percent of China's total exploration budget to 5.6 percent. Meanwhile, exploration in Africa expanded from 8.1 percent to 12.3 percent of the total. Overall, China has accumulated 16 percent ownership of world copper mining output.

Will China call the shots on global copper prices?

Recently, China’s NDRC announced that the State Reserves Bureau plans to hold auctions to release some of its strategic copper reserves. Copper prices dropped modestly in response but have stabilized since, as the small volumes being offered will not significantly ease demand. The muted market reaction may also be due to uncertainties surrounding frequency of these planned auctions.

However, this is not the first time that China has flexed its market power to influence global commodity prices. With China likely holding upwards of 2 million tons of copper in reserves, the market watches its every move. Will its industrial policies and ambitions hold sway over the price and availability of this “red metal” that is becoming indispensable to global decarbonization? Rather than waiting to find out the answer, the sooner governments develop strategies to hedge against China’s influence, the better.

(1) - https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/961711588875536384/Minerals-for-Climate-Action-The-Mineral-Intensity-of-the-Clean-Energy-Transition.pdf

(2) - https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2020

(3) - https://outlook.gihub.org/

(4) - https://insights.abnamro.nl/en/2014/10/copper-price-economic-indicator/

(5) - https://www.reuters.com/article/us-metals-copper-ahome-column/chinas-super-charged-buying-reshapes-the-copper-market-andy-home-idUSKBN2CM1G5

(6) - https://www.icsg.org/

(7) - https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2020/mcs2020-copper.pdf

(8) - https://copperalliance.org.uk/coverage-future-copper-demand/

(9) - https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-19/the-world-will-need-10-million-tons-more-copper-to-meet-demand?sref=ICRqgS18 (10) - https://me.smenet.org/webContent.cfm?webarticleid=3482

(11) - https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/chinese-foreign-mining-investment-8212-china-s-private-sector-eyes-low-cost-regions-63066809

(12) - https://www.iisd.org/itn/fr/2014/11/19/chinas-new-outward-investment-measures-going-global-in-a-sustainable-way/

(13) - https://gop-foreignaffairs.house.gov/china-regional-snapshot-south-america/

(14) - https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/chinese-foreign-mining-investment-8212-china-s-private-sector-eyes-low-cost-regions-63066809

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).