Published 01 October 2020

Past studies have found evidence to support the assertion that when faced with an election, politicians are more likely to take a protectionist stance. That trend has continued, or perhaps escalated, over the last 15 years.

Do as I say?

Trade rarely ranks high for voters in the election booth – so why do we seem to see an uptick in anti-trade sentiment around election time? And does protectionist rhetoric during the campaign season influence politicians’ actual voting behavior on trade?

Evidence, both anecdotal and academic, suggests yes – term length and the electoral calendar play a key role in determining the outcome of votes on trade policy. Members of Congress tend to believe that supporting more protectionist trade policy will increase their chances of re-election. Conversely, without that fear of repercussions at the ballot box, politicians vote in favor of more liberal trade policy.

In the words of economist Dani Rodrik, “no other area of economics displays such a gap between what policymakers practice and what economists preach as does international trade.” There are many examples of normally pro-trade politicians shifting their views around election time.

For example, in the run-up to the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama attacked NAFTA despite going on to go all-in on free-trade in his presidency. Similarly, in the 2016 Toomey vs. McGinty Pennsylvania Senate race, both formerly free-trade politicians changed their tune to try to appeal to more voters. Beyond the anecdotes, a group of economists has sought to study the pattern over years of trade votes in the United States.

A study into economic policy and elections

In their 2011 paper “Policymakers’ Horizon and Trade Reforms,” Paola Conconi, Giovanni Facchini, and Maurizio Zanardi attempted to empirically answer the question: Do imminent elections impact the decision-making and voting behavior of elected officials on issues related to trade?

Conconi, Facchini, and Zanardi compared the voting behavior of candidates facing an upcoming re-election contest with those who had a long term ahead of them. Senators are up for election every six years (meaning that every two years, one-third of all seats are up) whereas U.S. House members face election every two years. This vote log provides many data points that show changes in behavior of individuals over time, at different points in the election cycle.

The authors analyzed the individual roll call votes on the final passage of every trade liberalization bill introduced in the U.S. Congress between 1973 and 2005. They considered 29 votes in total, covering 15 trade reform bills. All but one of the bills was approved but with varying margins.

Closer to re-election, free trade voting tendency drops 10 percent points

First, the authors compared House and Senate members. Other studies have shown that House members are generally less likely to support trade liberalization than senators, and the authors’ results align with this. However, the authors found that there is no significant difference in the voting behavior between House members and senators during their last two years before re-election. This suggests that the intercameral difference between the two groups could be explained by their term length, rather than other factors such as constituency size.

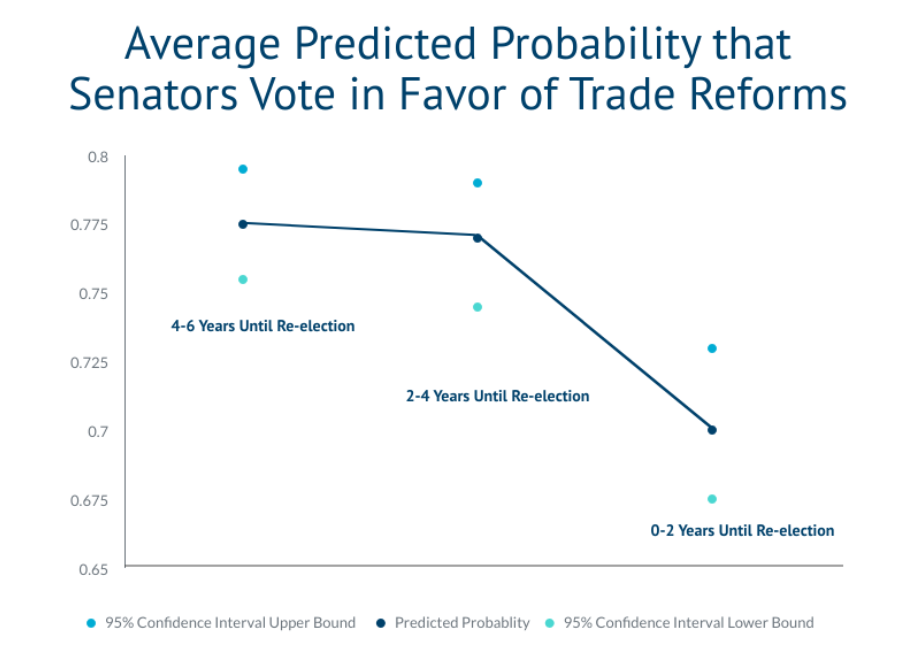

Next, they compared different generations of senators, finding that they become more protectionist the closer they get to a re-election campaign. Senators in the last two years of their term are around 10 percentage points less likely to vote in favor of trade liberalization policies than those in their first four years, a significant difference. Interestingly, Banri Ito, in his 2015 paper, used data from the Japanese House of Representatives election in 2012 to find similar results, indicating this is not purely an American phenomenon.

Safe seat, retirement or election defeat associated with free trade vote

Their results hold when studying the behavior of the same senator over time or comparing a whole host of controls including campaign contributions, age, gender, and party affiliation. Even those representing constituencies where a majority of their voters should benefit significantly from trade liberalization, such as heavy exporting constituencies, exhibit the same late-term protectionist tendencies.

In contrast, senators who are retiring or who hold very safe seats do not change their behavior as an election nears. Interestingly, two of the votes they tracked occurred in a “lame duck” session (after November elections but before the new senators had taken their seats). In those votes, no defeated senators voted against trade liberalization.

Overall, the Conconi, Facchini, and Zanardi study showed:

- Members of the US House are more anti-trade liberalization than US Senators, but that difference disappears during the last two years of a senator’s term.

- Election proximity reduces representatives’ support for trade.

- The protectionist effect applies both to senators who generally oppose liberalization (Democrats and import-competing constituencies) but also to senators who are generally more pro-trade (Republicans and export-competing constituencies).

- The inter-generational differences disappear for representatives holding safe seats or who are retiring (meaning a return to votes in favor of trade liberalization).

The tendency for politicians to vote in favor of free trade drops 10 percentage points closer to re-election.

Anecdotal evidence – Trade and elections today

Although far from sufficient to draw any concrete conclusions, anecdotal evidence does appear to corroborate findings from the Conconi, Facchini, and Zanardi study. We can find numerous examples of U.S. politicians changing their views on trade when the re-election stakes are high.

When votes on significant trade deals are on the table, trade has featured in congressional races, but in presidential races, trade is often a footnote or subsumed by debates over the state of the economy broadly. However, Donald Trump’s presidential campaign signified a marked change as he made trade a central part of his platform. In 2016, both Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton took a negative stance on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and Trump against NAFTA. Notably, as Secretary of State, Clinton had defended TPP as the “gold standard” of trade agreements, but expressed a different view during election season.

In the 2016 Pennsylvania Senate Race, support of the TPP became an extremely important issue between two politicians with records of trade-liberalization support. Republican Senator Pat Toomey and Democrat rival Katie McGinty both came out against the TPP, despite the former’s career-spanning support of free-trade deals, and the latter’s support of the then newly-signed NAFTA while she served in Bill Clinton’s administration.

Similarly, Republican Ohio Senator Robert Portman, who voted in support of NAFTA in 1993, a series of subsequent trade deals, and served as George W. Bush’s chief trade negotiator, came out against the TPP. Democratic rivals called the announcement an election-year conversion.

Some politicians even admit to changing their views due to the political climate. Rep. Luke Messer (R-IN) who went from supporting various free trade deals with China to opposing them, called his own reversal on the issue a reaction to changing political pressure.

As for the 2020 election, Biden and Trump both cite trade as a critical issue, saying that U.S. trade policy has not been benefiting Americans as it should. Biden seems to have moved away from his past pro-free trade stance, and both candidates are advocating for Buy American policies.

DNC & RNC platforms

Both the Republican and Democratic parties have taken on a protectionist bent ahead of the 2020 election, and in fact the platforms seem remarkably similar. Both the Democratic and Republican platforms emphasize the need to protect American workers from a competitive international system, with free trade and trade agreements taking a back seat. The Republican party is doubling down on its 2016 goals to punish China and bring outsourced jobs back to the United States, while the Democratic party touts the same goals, but proposes a new solution.

Democratic Party

In the 2020 Democratic Party Platform, any talk of free trade is notably absent, apart from a brief mention of support for the African Continental Free Trade Agreement and promoting free trade in that region. Instead, when trade is mentioned the focus is on China’s unfair trade practices and on the need to protect American workers from the global trading system.

The platform states that “Democrats will pursue a trade policy that puts workers first,” negotiating for labor, human rights, and environmental standards in trade agreements. They cite the COVID-19 pandemic as evidence that the United States has over-relied on global supply chains, but criticize the Trump Administration’s US-China trade war as un-winnable. On the issue of China, the Democratic party plans to take aggressive action against them, and any other country that takes unfair trade action such as dumping, currency manipulation, and unfair subsidizing, as well as theft of US intellectual property. The platform states that tax and trade policies that have encouraged corporations to move manufacturing jobs overseas and avoid taxes will be eliminated. They will “claw back” any public investments or benefits received by a company that shuts down US operations to move abroad.

The DNC’s discussion of “Global Economy and Trade” and “Advancing American Interests” focuses yet again on putting American workers first. They claim that no new trade agreement will be negotiated before first investing in American competitiveness, and existing trade laws and agreements will be aggressively enforced. They plan to work with allies to stand up to China, and negotiate from the strongest possible position. An outline is also given of their stance to fight foreign corruption, and to reign in “misused and overused” sanctions.

Republican Party

The Republican party decided to forgo a traditional platform this year, instead opting to “to enthusiastically support the president’s America-first agenda”. However, the party also agreed to adopt the same platform as in 2016. President Trump has released a list of core priorities for his second-term agenda, two of which – “Jobs” and “End Our Reliance on China” – contain goals directly applicable to issues of trade. Echoing the growing protectionist rhetoric, Trump’s priorities appear to double down and expand on the 2016 platform.

Under the core priority of “Jobs,” Trump vowed to “Enact Fair Trade Deals that Protect American Jobs” and implement “’Made in America’ Tax Credits”, sentiments that match up with Trump’s various executive orders focused on Buy American policies. The 2016 Republican platform recognized the importance of free trade deals: “We envision a worldwide multilateral agreement among nations committed to the principles of open markets, what has been called a ‘Reagan Economic Zone,’ in which free trade will truly be fair trade for all concerned.” The 2020 priorities seem to expand on this policy, stating that free trade is good, but with much more focus on the American worker and American power in the equation.

Another of Trump’s core priorities is to “End Our Reliance on China,” including goals such as “Bring Back 1 Million Manufacturing Jobs from China,” “Tax Credits for Companies that Bring Back Jobs from China,” and “No Federal Contracts for Companies who Outsource to China”. China was mentioned in the 2016 platform too, with the party vowing to take a firm stance that involved retaliation when necessary in order to punish Chinese “currency manipulation, exclusion of US products from government purchases, and subsidization of Chinese companies to thwart American imports.” Perhaps unsurprisingly given global politics, this again appears to be an area of increased focus for the Trump administration looking ahead to a second term.

Protectionist rhetoric on the rise

Past studies have found evidence to support the assertion that when faced with an election, politicians are more likely to take a protectionist stance. That trend has continued, or perhaps escalated, over the last 15 years – and if the rhetoric we’re seeing on the 2020 campaign trail is any indication, it seems unlikely to slow down anytime soon.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).