After a long era of trade liberalization, US trade policy under the Trump and Biden administrations has returned to “managed trade” measures, including tariffs, and a less discussed but no less interesting tool: quotas.

The difference between quotas and tariffs

Quotas and tariffs are both used to protect domestic industries by artificially raising prices in the domestic market. Their administration and effects, however, differ in specific ways.

Quotas can be much more complicated to administer than tariffs. Tariffs are collected by a customs authority as goods enter a country. With quotas, customs authorities must either monitor imports directly to ensure that no goods above the quota amount are imported, or for TRQs, that duties are applied to goods imported over the quota. Alternatively, customs authorities can award licenses to specific companies, giving them the right to import the amount allowed under the quota. Quotas can also take the form of a voluntary export restraint (VER), where the exporting country administers the quota.

While tariffs generate revenue that is paid to the importing country’s treasury, the value of a quota (quota rents) generally goes to foreign exporters, who can sell goods subject to the quota at higher prices and collect higher per-unit revenue. In both cases, domestic consumers in the importing country pay the costs of tariffs and quota rents. But with quotas, the importing country’s government receives no revenue.

The cost of quotas

World Trade Organization (WTO) consistency

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Article XI prohibits quotas and other quantitative restrictions as are overly distortive compared to duties, taxes, and TRQs. In fact, on December 9, 2022, a WTO dispute panel decided against the US, holding that its imposition of quotas on South Korea, Brazil, and Argentina is inconsistent with Article XI and that Section 232 tariffs and quotas on steel and aluminum do not fall under the “security exception”.8

Tricky to administer

South Korea, Brazil, and Argentina each agreed to product-specific absolute quotas on 54 separate steel articles based on each country’s average annual import volumes from 2015 through 2017. Argentina also accepted product-specific absolute quotas on two aluminum product categories.

The true cost in practice

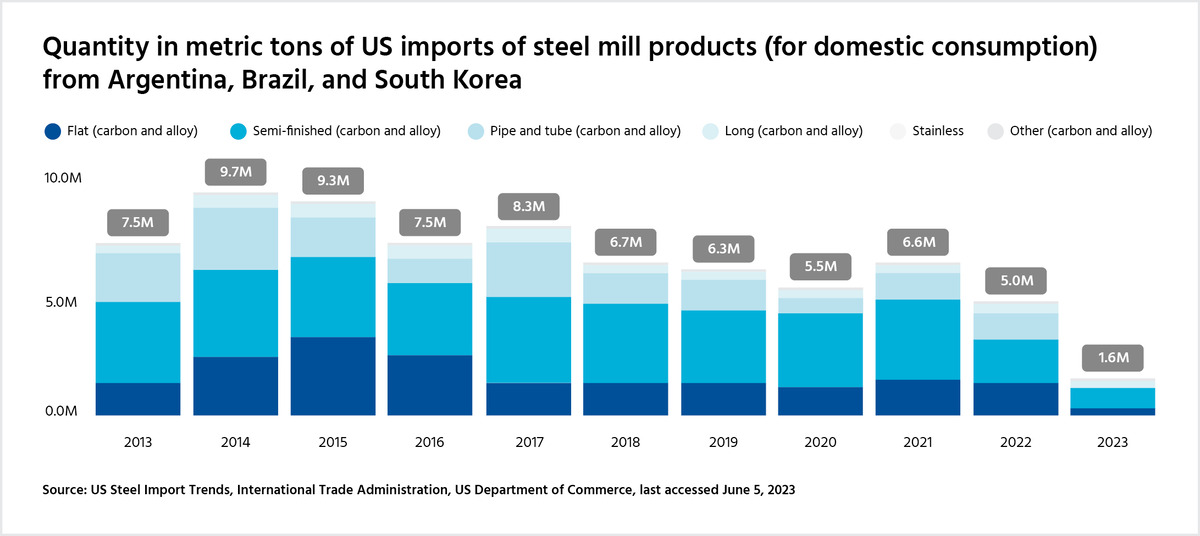

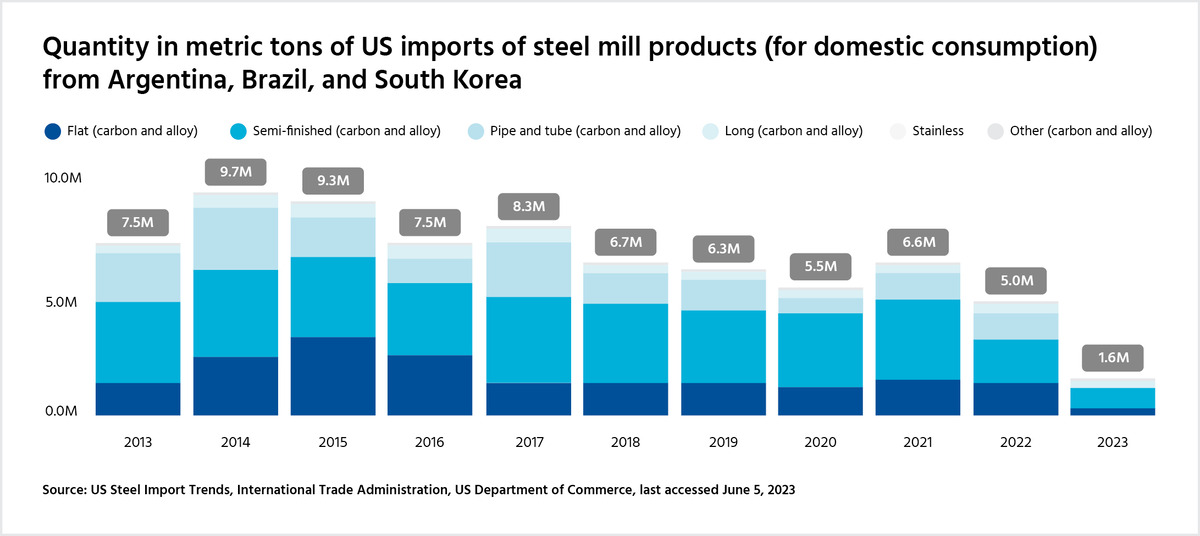

For South Korea, Brazil, and Argentina, quotas have reduced export volumes to the US, particularly due to the reduction in South Korea’s exports in line with the limitations imposed by the quota regime.

According to US Department of Commerce data, the overall quantity of steel South Korea, Brazil, and Argentina exported to the United States from 2018 to 2022 has dropped compared to the annual level of imports during the previous five-year period.9

Upside for US steel producers

For US steel and primary aluminum producers, Section 232 tariffs, and to a limited extent quotas, are accomplishing their goal of bolstering US manufacturing capacity and creating conditions for US manufacturers to expand production and enjoy higher prices.

A 2023 US International Trade Commission (ITC) study examines the economic impact of Section 232 tariffs, broadly accounting for quotas. According to the study10, Section 232 restrictions reduced steel and aluminum imports by about 24% and 31.1% while US production increased by 1.9% and 3.6%, respectively, from 2018 to 2021. Tariffs may have increased the average price of US steel and aluminum by 2.4% and 1.6%, respectively.

Downside for downstream industries

It’s a different story for US downstream manufacturers, who say quotas have entailed “severe supply constraints” and “created even more business uncertainty than tariffs”.12

Importers may no longer guarantee that their goods can enter under the quota, or at all. They may encounter unanticipated costs if the quota is filled while goods are in transit or unpredictably higher prices for goods subject to a quota. They may have to find new suppliers and bear all the costs of negotiating new contracts, building new relationships, and shipping from a new location. The exclusion process may provide some relief for importers under supply pressure, though its application may also introduce more uncertainty.

More generally, downstream manufacturers argue that Section 232 quotas and tariffs raise prices inhibiting their competitiveness, and have a chilling effect on growth, employment, and investment. Although many businesses have been buoyed by the strong US economy, they say that employment and sales in their industries would have increased even more were it not for tariffs and quotas raising prices. Moreover, downstream industries using steel and aluminum products employ more Americans than steel and primary aluminum manufacturers.

In fact, the 2023 ITC study found that for downstream industries, the impact of Section 232 tariffs was largely negative.13

Addressing global excess capacity is key

Though in general, the Biden administration has embraced the Section 232 quotas14 and tariffs,15 in late 2021 and early 2022, the Biden administration negotiated agreements with the EU, Japan, and the UK to lift Section 232 tariffs in favor of TRQs.

As part of its negotiations with the EU, the Biden administration has also proposed a Carbon-Based Sectoral Arrangement on Steel and Aluminum Trade.16 While promoting the trade of steel and aluminum produced with fewer carbon emissions, the arrangement would establish barriers to goods produced with higher carbon emissions, an effort that also targets excess capacity in steel and aluminum production.17

Though they are not fully liberalizing, these agreements represent a stepping away from more restrictive tariffs and absolute quotas and lifting retaliatory tariffs while focusing on the underlying cause of US industry distress—global excess capacity.18

Though tariffs and quotas may provide short-term relief, solving underlying global excess capacity problems is critical to addressing US industries’ long-term challenges. Any long-term solution will require more than the mere application of protectionist measures. The United States will have to work closely and creatively with its trading partners to address this challenge directly and to persuade the world’s largest producers, including China, to reduce global excess capacity.

Holly Smith is a lawyer and consultant. From 2009 to 2015, she served in the Office of the United States Trade Representative as a Director for Intellectual Property and Innovation, a Director for China Affairs, and a senior policy advisor to the Deputy U.S. Trade Representative.

***

[1] Adjusting Imports of Steel Into the United States, Federal Register

[2] Adjusting Imports of Steel Into the United States, Federal Register

[3] Adjusting Imports of Aluminum Into the United States, Federal Register

[4] Announcement of Actions on EU Imports Under Section 232, USTR

[5] A Proclamation on Adjusting Imports of Steel into the United States, White House

[6] Ibid

[7] Economics of Tariff-Rate Quota Administration, ERS

[8] United States – Certain Measures on Steel and Aluminium Products, Report of the Panel, World Trade Organization

[9] Global Steel Trade, International Trade Administration

[10] Economic Impact of Section 232 and 301 Tariffs on U.S. Industries, USITC

[11] U.S. aluminum trade group calls on Trump to avoid quotas, Reuters

[12] Trade Letter: Tariffs Have Caused ‘Significant Harm to Manufacturers’, Industry Week

[13] Ibid

[14] U.S. not looking to renegotiate Trump-era steel quotas with S.Korea, says Raimondo, Reuters

[15] Lifting Tariffs on Goods May Make Sense, US Commerce Chief Says, Bloomberg

[16] FACT SHEET: The United States and European Union To Negotiate World’s First Carbon-Based Sectoral Arrangement on Steel and Aluminum Trade, White House

[17] US Commerce chief says green steel pact would combat excess Chinese output, Reuters

[18] The problem with U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum that no one is talking about, Hinrich Foundation

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).