Published 07 May 2024

Foreign investment has had a disproportionally large impact on the dynamism of the Chinese economy, largely due to the value of foreign ideas that came with FDI and used to drive China’s domestic efficiencies and technological advances. As Beijing tries to stop the rot in its economy but foreign companies will not return, the government's worst – but perhaps likeliest – response would be to further isolate China from the global market.

The collapse of inbound foreign direct investment (FDI) to China has attracted much attention. In the third quarter of 2023, according to data released by China’s State Administration for Foreign Exchange (SAFE), foreign companies actually pulled more money out of China than they put into it: inbound FDI was negative for the first time on modern record. For the whole of 2023, the number was positive to the tune of US$43 billion, equivalent to just 0.2% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) and down 77% year-on-year.1

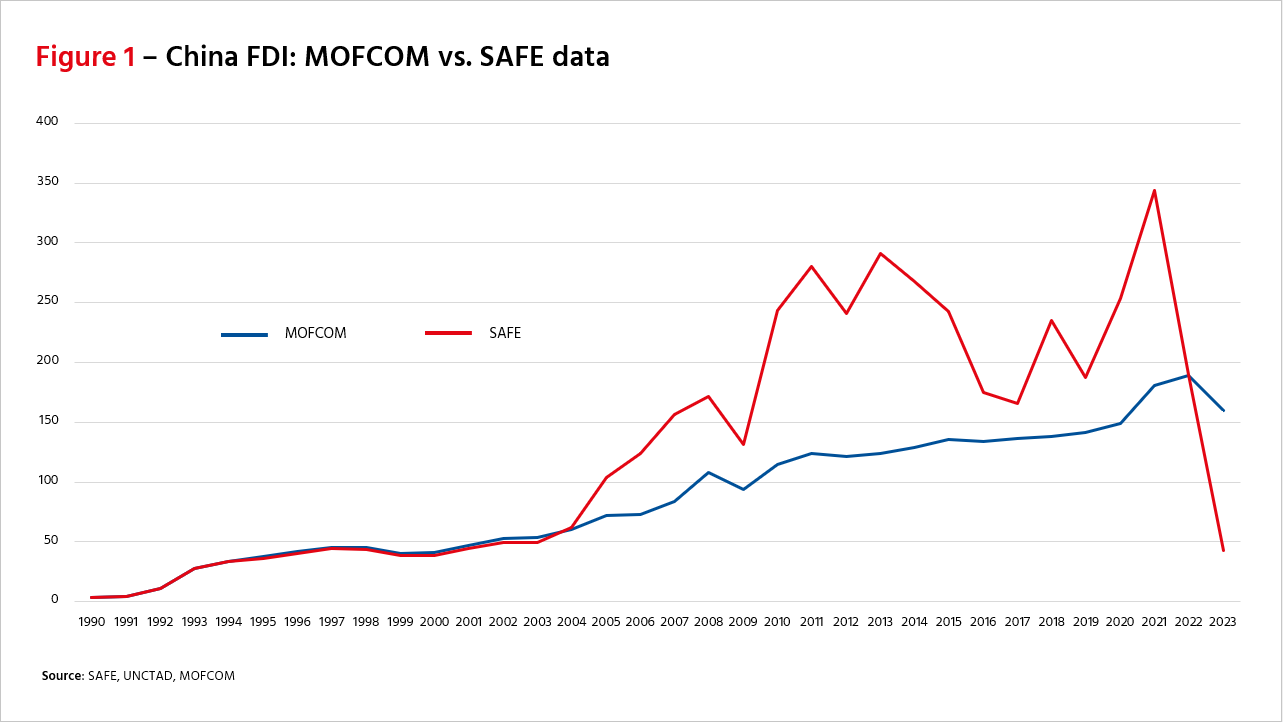

China produces two sets of official FDI statistics based on different methodologies. The SAFE number is produced on a net basis, i.e., it takes account of foreign firms pulling capital out of China; includes some inflows such as regulatory purchases of bonds required by financial companies to comply with capital requirements; venture capital and private equity investments where these lead to a substantial change in foreign ownership; and money raised in offshore capital markets by China- related firms.2 China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) also publishes FDI data but uses a gross figure that does not include the categories listed above. There is also a timing lag between the two sets of data in the accounting of retained profits, which further set them apart.

The MOFCOM data on China’s inbound FDI was not as dire as the SAFE data for 2023 as it did not capture outflows by foreign-funded companies divesting from China. Equally, as the chart below shows, it was never as high as the SAFE data in recent years because it does not capture regulatory inflows nor the private equity and offshore listing inflows. Nevertheless, the MOFCOM data shows gross FDI falling in 2023 to about US$160 billion after a prolonged period of relative stagnation even in nominal terms.

China’s 2023 FDI data needs to be put in context. 2023 is the first year in which SAFE posted inbound FDI data at a level below MOFCOM data, demonstrating that the foreign firms exiting China has been a more influential factor than inflows that have historically augmented the SAFE number. It seems likely that about US$100 billion of foreign FDI left China in 2023.

In addition, as the chart below shows, net inbound FDI relative to China’s GDP has been in a continual downtrend since 1994 when it was almost 6% of GDP. In a country where investment comprises over 40% of GDP, the foreign component is small when measured in purely quantitative terms. This, combined with the fact that China has consistently saves more than it invests, and is therefore not constrained by a lack of foreign capital, has led some commentators to dismiss the fall in FDI as being economically irrelevant.

It is not irrelevant.

So what?

The fall in FDI has been attributed to several factors. Increased geopolitical tensions have created an atmosphere in which corporates are more circumspect on the risks that the geographic location of their facilities carries. The pandemic highlighted the vulnerabilities that excessive concentration of supply can bring. China’s falling growth rate has additionally tarnished the appeal of investing there, based purely on future expected returns. And there is a perception that the business environment in China has become trickier to manage in the light of new security-related laws.

However, perhaps the real cause for concern is that FDI has had a disproportionally large impact on the dynamism of China’s economy. While it may be true that a change of perceptions on China’s future growth prospects has reduced China’s appeal as an investment destination. It could also be the case that reduced FDI has dimmed the growth prospects for China: the causation runs both ways.

Consider for example the fact that, between 1996 and 2010, foreign companies accounted for more than 50% of China’s exports by value. This share has been in structural decline but remains significant at just below one-third now. In addition, foreign companies enjoy profit margins about 15% higher than their Chinese counterparts, implying greater capital efficiency. For example, in 2022, foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) accounted for 20.7% of industrial enterprises’ business revenue but 23.8% of profits. That compares to 2005 when FIEs accounted for 31.6% of revenue but 28% of profits. From a fiscal standpoint, FIEs are also very important, accounting for 17.6% of national tax revenue in 2022.3

Two trends stand out: Foreign participation in China’s economy is more efficient and creates more value than its domestic counterparts, but is also in relative decline. The total stock of foreign investment remains substantial, which implies that its continued decline will exert a long-term drag on China’s overall growth.

As things currently stand, using SAFE’s international investment position data, China’s stock of inbound FDI grew at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16% in the ten years through to 2016. But by 2023, that ten-year CAGR had dropped to just 4%. This is an important but overlooked driver of China’s structural slowdown.

Furthermore, if the trend continues – It’s perhaps too soon to say they definitely will –China runs the risk of being increasingly divorced from growth in foreign supply chains. This may seem an odd thing to suggest when it is currently still so central to global supply chains, but China’s centrality occurred relatively quickly. The reverse could happen just as quickly if China becomes effectively isolated from the foreign ideas that drive its domestic technological advances and other spillover impacts of FDI on domestic efficiencies.

Innovation is not just driven by foreign companies, but by Chinese ones too. Chinese firms looking to maximize profit would seek to reduce costs and stay connected to foreign customers, suppliers, and related ecosystems by moving offshore. This would compound the flight of FDI – and the power of ideas that economic growth requires – from China.

When looking at China’s net inbound FDI relative to its net outbound FDI, it is interesting to note that, in both 2022 and 2023, outbound flows exceeded inbound flows. This has happened only once before – in 2016 – when it was accompanied by a brutal round of centrally-directed tightening of capital controls to head off a systemic economic collapse by preventing capital from leaving China. As China tries to stop the rot in its economy but foreign companies will not come back to China, Beijing’s worst – but perhaps likeliest – response might be to stop Chinese companies from joining global supply chains overseas.

***

[1] https://www.safe.gov.cn/en/2024/0218/2175.html

[2] See: Nicholas Lardy: Foreign direct investment is exiting China. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/foreign-direct-investment-exiting-china-new-data-show

[3] http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/wzs/202310/20231010105622259.pdf

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).