How to use it

Trade in services for development: Fostering sustainable growth and economic diversification

Published 23 January 2024

The importance of services to economic growth throughout the world cannot be understated. This report from the WTO and World Bank identifies and emphasizes how regulations and policies can contribute to the growth of trade in services.

Here’s how to use the report entitled Trade in services for development: Fostering sustainable growth and economic diversification.

Why is the report important?

Although services generate more than two-thirds of global GDP (p. 2), many policy-makers continue to prioritize manufacturing and trade in goods over promotion and liberalization of trade in services. This report makes an important contribution in making clear the vital role that services play in economic growth, and their increasingly important role in global trade, as well as their contributions to economic development around the world.

What’s in the report?

The report includes three principal sections:

Introduction; The future of trade lies in services: key trends

- Services have been the main source of economic growth since the 1990s and dominate the production and employment landscape of economies at all levels of development; services account for 50% of global trade in value-added terms and 67% of global GDP; 54% of global services exports were digitally delivered in 2022. (pp. 8-11)

- Services generate more jobs and output than agriculture and industrial sectors combined; services share of global GDP increased from 53% in 1970 to 67% in 2021; services shares of global employment increased from 40% in 2000 to 50% in 2021; these trends are most pronounced in upper middle- and high-income economies but also present in low-income economies, where agriculture continues to play a significant role. (pp. 14-16, Figures 2 and 3)

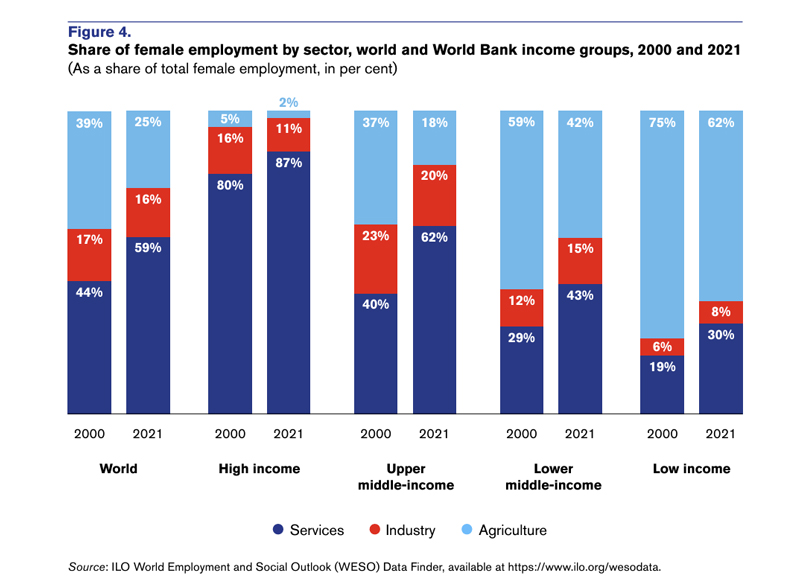

- Services play an important role in employment and empowerment of women and youth; in 2021, 59% of women worked in services compared to 44% in 2000; the share of women employed in services has increased in all economies since 2000. (pp. 17-19, Figures 4 and 5)

- Services have long been portrayed as non-tradeable activities characterized by low productivity and wages, but are seen increasingly as determinants of productivity, competitiveness, and rising living standards; the growing contribution of services to economic transformation is linked to their increasing tradability and the greater contestability of services markets; government policies on services trade are key to spurring services-led growth and development. (pp. 20-21)

- Services are a large and growing share of world trade, forming 22% of global trade flows in 2022, a share increase of 170% since 2005; developing countries’ share of global commercial services exports has increased from 23.5% in 2005 to 33.5% in 2022; growth is driven by advances in ICT and digitally-delivered services. (pp. 21-22, Figures 6-7)

- Growth in less traditional sectors like ICT, or ‘other commercial services’, many of which are digitally delivered, have expanded at a much faster rate than traditional sectors like transport and travel; ICT services growth has been particularly strong in developing economies, accounting for a growing share of their services exports. (pp. 23-25, 28-29, Figures 8-11)

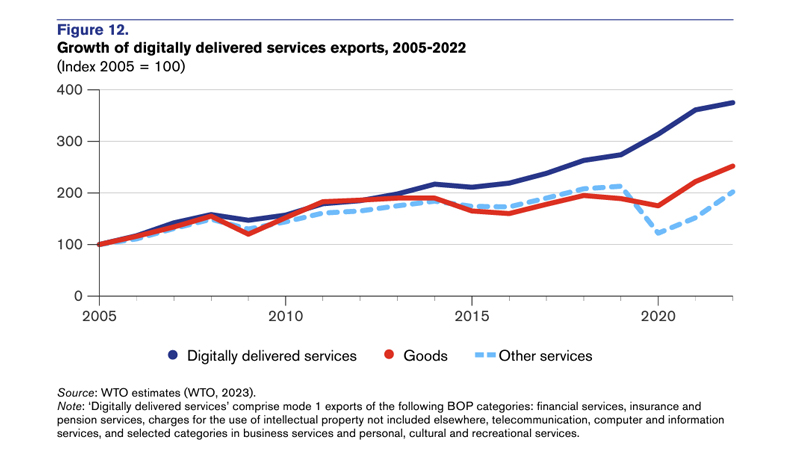

- Global exports of digitally delivered services have tripled since 2005, reaching US$3.82 trillion in 2022, a 54% share of global services exports; Europe accounts for more than half of global exports of digitally delivered services, with Asia growing faster than the rest of the world, and Africa and least developed economies lagging in exports in this sector. (pp. 30-31, Figure 12)

- Growth of cross-border service trade has increased the number of jobs linked to services exports, including in developing economies; these jobs represent a large and rising share of economies’ total services jobs, and in some economies, of total employment; the share of jobs linked to services exports has increased overall. (p. 35, Figure 13)

- Micro, small, and medium enterprises play a key role in services trade and account for the greater share of total cross-border services exports in a range of economies; the pandemic caused a collapse in cross-border services trade, reinforcing and accelerating changes to trade patterns already underway by boosting the importance of services that can be supplied digitally, and exposing digital divides within and across countries. (pp. 36-38, Figures 14-15)

- Balance of payments statistics fail to measure services provided by foreign-owned companies operating in another economy; when measured, services share of world trade increases by 20%, representing 43% of global trade in goods and services; when all 4 modes of services trade are measured, developing economies’ share of global services trade increases to 25.2%, due to the services provided by companies from China, Hong Kong, India, and Singapore. (p. 40, Figure 16)

- Services play a critical role in enabling the emergence of regional and global value chains; services have become important inputs at all stages of production of goods and services; 69% of global services trade is in intermediates; while services in value-added terms accounted for 50% of global trade, in gross terms, services accounted for 25% of global trade in 2018; even in economies where services represent a small proportion of total exports in gross terms, services value-added accounted for a significantly larger share of total exports. (pp. 41-44, Figures 17-21)

The contribution of services trade policies

- Impediments to trade and investment in services shield domestic suppliers from competition, leading to higher prices and reducing incentives to invest, innovate, and improve; sectors facing lower trade costs tend to be more productive and have higher productivity growth; in developed economies, services policies can explain differences in total factor productivity and productivity growth; trade restrictions negatively affect performance in services sectors. (pp. 48-49)

- Services trade restrictions reduce foreign investment inflows and lower output of foreign affiliates; deterrent effects of barriers to foreign investment are larger in the services sector; investor confidence and FDI flows increase with reduced regulatory risk. (pp. 51-52)

- Openness in services trade increases productivity and exports in manufacturing; services trade restrictiveness, including on inward FDI, has a negative impact on manufacturing exports, including on their sophistication; policy restrictions raise costs, limiting cross-border services trade; higher restrictions lower shares of services value-added within GVCs. (pp. 53-54)

- Telecommunications and computer services, including the Internet, allow digital supply of services; countries with effective pro-competition regulations are more successful in stimulating market growth and digital readiness; higher entry barriers and restrictive regulations on services mean less investment in digital technologies and ICT and less ICT development; restrictive data policies result in fewer imports of data-intensive services. (pp. 55-58, Figure 22)

- Policies that enable services and services trade aid in women’s economic empowerment and can help economies transition to a low-carbon economy and meet UN Sustainable Development Goals; restrictive policies inflate costs and reduce access to environmental goods and services; climate change will trigger many adjustments in economic activities; countries with greater openness to trade can better adjust to climate-induced shocks. (pp. 58-60, 64-65)

- Access to services increasingly matters to agriculture production and exports; services sector inputs account for 30% of the final value of agri-food products in high-income economies, and 23% in middle- and low-income economies; the contribution of services to agricultural production and exports is increasingly linked to digital services designed to make agriculture more efficient allowing greater access to timely information and resource sharing. (pp. 62-63)

- Sustained diversification of an economy relies on services; sound services trade regimes are key parts of a policy framework and business climate facilitating competition and investment in new activities, boosting private sector expansion, and speeding up reallocation of resources toward higher productivity activities; leveraging digital, business, and financial services is key to driving structural transformation. (pp. 63-64)

- Barriers to trade and investment in services remain high overall, with variations across sectors, modes of supply, regions, and levels of development; trade restrictions on sectors vital to the movement of goods and supply of services – transport, telecommunications and computer services – remain high and were tightened during the pandemic. (pp. 65-66, Figure 23)

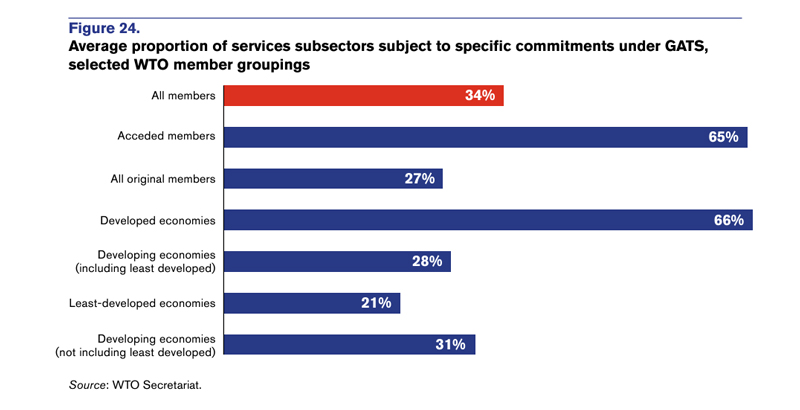

- Under WTO rules, market access commitments are more limited for services than goods; since 1997, WTO members have not improved their market access commitments for services and have made limited use of GATS to lower services trade restrictions or guarantee existing levels of access to ensure greater policy predictability and circumscribe trade restrictive measures; commitments under preferential trade agreements (PTAs) covering services have grown at a fast pace and parties have undertaken significantly higher commitments than in multilateral agreements; services commitments binding the regulatory status quo generate more trade than commitments with a gap between bound and applied restrictions. (pp. 67-66, Figures 24-26)

How to apply the insights

-

This section makes the case, supported by facts from independent research, that reducing restrictions on services trade and adopting policies to enable healthy services growth can increase economic growth, productivity, and exports across a range of sectors, and additionally enable social goods like women’s empowerment and combatting climate change.

-

The discussion also provides specific examples from Chile (Box 7), East Africa (Box 8), Gabon (Box 10), and Central Asia (Box 11), illustrating successful efforts to liberalize, develop, and allow services to play a helpful role in economic growth and development.

-

Policymakers can refer to this section to support arguments for further liberalization of services regulations and services trade.

Fostering economic development through services trade

- Economies should deepen international cooperation by negotiating trade agreements to secure services sector reforms; trade agreements with binding commitments allow governments to demonstrate credibility of domestic reforms, enable reciprocal services liberalization among parties, enable diversification of services exports, encourage greater investment in services sectors, increase participation in supply chains, and access technical and financial assistance negotiated in agreements. (pp. 74-76)

- Services are subject to high-levels of regulation, so building capacity to regulate and enforce services rules is critical; technical support directed at building regulatory frameworks is important; trade agreements can help, as can the Reference Paper on Services Domestic Regulation, agreed to by 69 WTO members in 2021; if completed, the Investment Facilitation for Development Agreement (negotiations launched in 2020) could complement members’ efforts to attract investment. (pp. 76-78, Box 12)

- Aid for Trade focused on services could support domestic reform efforts, address challenges developing and least-developed economies face in services trade negotiations, implementing negotiated outcomes, and exporting services to the global market; aside from disbursements directed at banking and finance, all other Aid for Trade disbursements directed at services trade have remained unchanged or decreased in the last 15 years. (pp. 73, 78-81, Box 14)

- Increases in Aid for Trade should be accompanied by a trade services for development initiative that:

- improves the availability of services-related data and policy-relevant information, with more funding directed to technical assistance and statistical capacity building (pp. 82-83);

- strengthens developing economy participation in international discussions on services trade by improving domestic analytic and strategic planning capabilities, government negotiation and coordination efforts, and implementation of agreements (pp. 83-85);

- audits existing domestic measures affecting services trade to improve transparency and prospects for negotiations and reform (pp. 85-87, Box 16);

- strengthens regulatory capacity and facilitates mobility of capital and labor, and assists in designing reforms that consider distributional impacts of services trade (p. 87);

- accelerates the pace of digitalization, requiring investments in ICT hardware, software, and digital literacy, and a conducive legal, regulatory and institutional enabling environment for ICT services (pp. 88-90); and

- boosts supply capacity and skills relevant to services trade, including by improving access to technology and financing, improving domestic services standards, training and skills, opening markets, and enhancing capacity of private actors. (pp. 90-92)

- To unlock the benefits of expanded services in trade, governments should recognize:

- Services have the potential to transform economies - the difference that services can make to growth and development warrants greater policy attention;

- Trade in services can benefit from increased international cooperation to increase predictability of policies and commitments of trade agreements, promote trade-facilitating regulatory practices, and lower barriers to trade in services;

- Multilateral engagement can strengthen services trade governance, including through plurilateral discussions at the WTO on services regulations, e-commerce, and investment facilitation; and

- Mobilization of additional resources, including through a services for trade development initiative, is critical to strengthening services trade capacity. (pp. 94-95)

How to apply the insights

- This section is useful in providing tools and ideas for regulatory and practical reforms that, even if not tackled multilaterally, domestic policymakers can undertake for improving their regulatory regimes for services trade.

- This section also underscores the efforts already underway at the WTO to address many of the challenges identifies, and compiles resources already available for understanding current regulations, best practices, and regulatory differences between economies.

Conclusion

The Trade in services for development report contains useful statistics, data, anecdotes, and ideas for understanding the role services play in global trade and economic development, especially for developing and least-developed economies. It is a helpful resource for any policy maker considering approaches to trade in services and services liberalization.

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- The rising role of services in global trade

- Prepare to pay more for digital services

- E-commerce and LDCs: The different speeds of greater integration

External Resources

- Trade Policy Tools for Climate Action – World Trade Organization

What trade policy tools can help to combat climate change and reduce carbon emissions? - Digital Trade for Development – IMF, United Nations, OECD, World Bank Group, and World Trade Organization

A report focused on the benefits and opportunities digital trade affords for developing economies. - World Trade Report 2023: Re-globalization for a secure, inclusive, and sustainable future – World Trade Organization

Trade fragmentation threatens to unwind growth and development.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).