How to use it

Securing semiconductor supply chains

Published 18 July 2023

Semiconductors, or chips, are a critical component for both advanced technologies and products used in daily life, and as such are the subject of intense focus among policymakers and companies relying on access to this key technology. This brief from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) explains the complexities of geopolitics snarling these supply chains.

Here’s how to use the Securing semiconductor supply chains: An affirmative agenda for international cooperation.

Why is the Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains brief important?

Pandemic-related chip shortages made plain the importance of access to reliable supplies of both low-end and high-tech semiconductors to the US economy and to US national security. The United States is also pursuing a strategy of restricting China’s access to critical technologies with military applications, particularly high-end dual-use chips. Consequently, US policymakers are intensely focused on semiconductor production, investment, R&D, and control over these technologies. As the US is currently in the process of seeking closer ties to like-minded nations to secure its chip supply chains, this brief’s assessment of potential partners is an important contribution to their efforts to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each country.

Introduction

- Semiconductors are integral components of both civilian and military use products; tensions between economic gain and security risk are heightened in fields with national security implications; how the government and private sector manage semiconductor global value chains (GVCs) will directly affect US global competitiveness and national security. (p. 1)

- The pandemic underscored the importance of semiconductors to the US economy; stagnated investment, inadequate input supplies, and logistics breakdowns led to a shortage. (p. 1)

- As US perceptions of China have changed, calls to lessen reliance on China and for “friend-shoring” have grown; the US should seek closer collaboration with countries with policies to support technology development and whose export controls are consistent with the US. (p. 2)

- The US is already pursuing collaborations with the EU through the Trade and Technology Council; with Japan, Australia, and India through the Quad alliance; and with Indo-Pacific economies through the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. (pp. 2-3)

The Global Semiconductor Value Chain

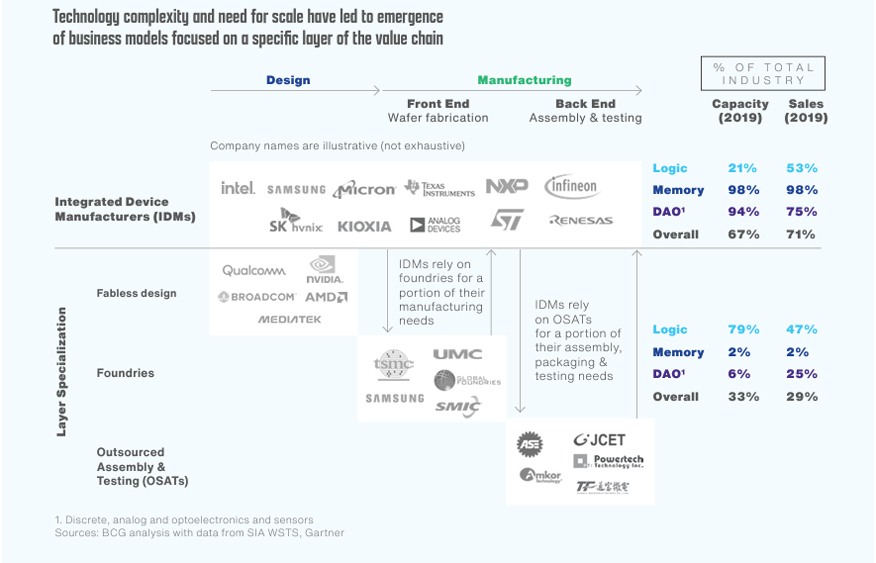

- Semiconductor GVCs are dominated by the US, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Europe, and China; the GVC consists of three main stages: R&D and chip design, fabrication, and advanced testing and packaging; R&D and chip design require substantial funding and human capital; fabrication involves a deeply technical process and significant capital expenditures. (p. 4)

- The fabless foundry model allows firms to specialize in one aspect of the GVC and outsource manufacturing; back-end manufacturing is done by outsourced semiconductor assembly and test (OSAT) companies of which Taiwan has a 53 percent share; assembly, testing, and packaging (ATP) companies are concentrated in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. (pp. 4-5)

- The integrated device model (IDM) is a vertical integration of semiconductor GVCs; it is only practiced by a few firms that enjoy higher profitability due to greater efficiency. (pp. 5-6)

Semiconductor Policy in the United States

- Diversification of GVCs reduces costs and the likelihood of major disruptions; while the US remains a leader in the design, lack of production capacity and continued reliance on foreign manufacturers restrains industry growth; high labor costs and insufficient government support for R&D have led to a decrease in the US share of chip manufacturing. (p. 6)

- The US has identified the production of chips as a top priority; new laws allocate billions of dollars to support increased semiconductor production and R&D. (p. 7)

- Trade policy facilitates the development of a resilient semiconductor industry; policymakers must ensure that industry growth does not conflict with the protection of national security; available tools include the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 and the Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR), both of which restrict exports and sales of critical technologies; export control effectiveness depends on enforcement by US trading partners. (pp. 7-8)

- Trade and investment policy must consider the global nature of semiconductor GVCs and available foreign alternatives to sensitive products; without close policy coordination on export controls, adversaries will be able to acquire technologies of concern; building secure semiconductor GVCs requires multilateral cooperation among semiconductor producers and for companies to make investment decisions consistent with these policy priorities. (pp. 8-9)

Semiconductor Policy in EU Member States

- The EU has become dependent on foreign producers, including China, for semiconductor production; the EU is adopting a law – the European Chips Act – to bolster R&D and production in Europe; state aid envisioned under the law may mean that companies will receive added benefits when partnering with the EU on semiconductor supply chains. (pp. 9-10)

- These EU member states are best positioned for increased US semiconductor collaboration:

- Belgium is a top player in the global semiconductor R&D supply chain, home to top research universities and one of the world’s top semiconductor R&D institutes, though it has a shortage of STEM labor that limits its high-tech potential. (pp. 11-12)

- The Netherlands is a semiconductor powerhouse with a fully integrated vertical semiconductor supply chain including applied research, chip design, chip architecture, chip production, and system integration and applications; it is highly competitive for business, has high levels of education, is well-located, has good infrastructure and has proven to be a good US partner, though it will contend with both political pressure from the US Government and the attractiveness of the Chinese market. (pp. 12-13)

- France has a significant presence in the European semiconductor industry with centers for R&D, manufacturing, and packaging; its industry receives support both from the EU and domestic initiatives; it is an innovation hub, is one of the world’s largest economies, is well-located and has good infrastructure; France also has access to critical mineral reserves; regulations and bureaucracy, however, can restrain the French market. (p. 14)

- Italy has the third-largest economy in the EU with several large manufacturing sites for a diverse set of chip components; however, it has poorer economic performance and inefficient government, spends less on R&D, has a less-educated workforce and government instability, and has a complicated relationship with China. (pp. 15-16)

- Germany is the world’s fourth-largest economy; fourth-largest exporter and fourth-largest importer of semiconductor devices; it is key to semiconductor production due to its production of key inputs; it has advanced R&D, a pro-business climate, established supply chain linkages and the policy to enforce due diligence, a strong industrial base, and a stable domestic government. (pp. 16-18)

- The EU is an attractive partner for the US in building resilient semiconductor GVCs due to its single market, financial support for semiconductor industry development, close cooperation with the US on tech policy and export controls, and geographic proximity to the US; its relations with China create complications because of the ambivalence of the EU’s approach. (pp. 18-19)

How to apply the insights

-

This section is useful for understanding the EU’s efforts to strengthen and grow its capabilities in semiconductor manufacturing, as well as key countries’ current capabilities, strengths, and weaknesses in semiconductor production. It also provides an interesting lens for considering what the US should look for in assessing which countries would serve as the best partners for building a resilient global supply chain for semiconductors.

Quad Cooperation

- India is a major growth market, importing nearly all of its commercial semiconductor products; it has specialized in chip R&D and design due to its large population of chip designers and highly skilled IT and engineering workers; India has only two fabs that produce for defense and space use; it has pledged significant funding for building chip production, but systemic issues like water and power shortages disincentivize new investment. (pp. 19-20)

- Japan is the world’s fourth-largest market for semiconductor manufacturing and equipment sales; it has the world’s most semiconductor factories, but does not have the high-tech capacity to produce cutting-edge chips due to its focus on vertical integration model, delay in embracing digitalization, focus on memory chips rather than computing power, and lack of public investment; its strength is in deep industrial expertise in semiconductor materials and its government’s renewed focus on boosting and diversifying its industrial capacity. (pp. 20-22)

- Australia’s chip production is limited to specific applications; it is largely a consumer of chips; its potential strengths lie in design capabilities in specific applications and its access to abundant silica deposits; it lacks the direction, experience, and commercial drive to develop semiconductor production capacity. (p. 22)

Recommendations

- The US and its allies should a) identify the goals they seek to achieve through friend-shoring supply chains while dampening the ability of foreign adversaries to gain a competitive edge; b) collaborate on smart, targeted investments that bolster innovation; c) work together to issue consistent, predictable policies; and d) create a new Information Technology Agreement to reduce tariffs on ICT goods. (p. 23)

- The US should avoid blanket export controls that risk dampening investment and next-generation R&D efforts; the US and its allies should consider creating a mini-regime similar to the Wassenaar Arrangement to coordinate and codify new technology controls; the US should institutionalize collaboration with the EU to avoid duplication and ensure resiliency. (pp. 23-24)

- The EU member states and Japan are the best candidates for friend-shoring US semiconductor supply chains based on what EU and Quad countries are currently producing and their alignment with US export control policy; the best candidates in terms of supply chain security and resiliency are Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. (pp. 24-25)

How to apply the insights

-

This section gives practical and straightforward recommendations for policymakers to use in developing secure and resilient semiconductor GVCs, given the complexity and global nature of GVCs and the fact that no country can develop semiconductor GVCs unilaterally.

Conclusion

At a time when major world economies are intensely focused on access to semiconductor production and development, the Securing Semiconductor Supply Chains brief provides a helpful assessment of key potential partners for the effort to develop secure and resilient supply chains among like-minded nations.

Complementary reports and analysis

Hinrich Foundation

- Chipping away at global semiconductor supply chains

- Will US semiconductor restrictions on China backfire?

- CHIPS Act: “Winning the 21st century” or wasteful industrial policy?

External Resources

- Four Asian Countries Lead in US Chip Diversification Move – Bloomberg

Thailand, Vietnam, India and Cambodia have seen significant increases in semiconductor exports. - Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution – The White House

The Biden administration aims to entwine domestic and foreign policy more deeply. - Chip Funds for Underdogs or Chaebols – Comparing Korea and the US – Chip Capitols

A deep dive into South Korea’s domestic chip policymaking. - Japan and the Netherlands Announce Plans for New Export Controls on Semiconductor Equipment – Center for Strategic and International Studies

Coordinated actions against China on semiconductor equipment.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).