Published 24 January 2020

Trade agreements promote rule of law, which in turn enables private economic activity to thrive. When coupled with commitments to market access, individuals and companies are free to do business anywhere in the world.

Trade agreements promote rule of law

One could argue that the fundamental goal of any trade agreement is to promote and undergird government adherence to rule of law, which in turn enables private economic activity to thrive. When coupled with commitments to market access, individuals and companies are free to do business anywhere in the world.

Trade agreements such as the newly congressionally approved United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement contain provisions designed to directly combat corruption and promote good regulatory practices. They also contain myriad requirements that support best administrative practices including publishing changes to regulations, allowing for public comment, and adhering to transparent processes for government tenders, for example.

What is rule of law where trade is concerned?

No country gets it perfectly right. Supporting rule of law requires vigilance, upkeep and continual improvement.

Impartial review and scrutiny can be a powerful incentive for self-reflection. In 2013, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce launched an effort to measure the qualities that companies look for “to make good investment and operating decisions...in any given market.”

Its resulting Global Rule of Law and Business Dashboard identified five broad factors to assess rule of law: transparency, predictability, stability, accountability and due process. Are the laws and regulations applied to businesses operating in the market readily accessible, easily understood, and applied in a logical and consistent manner? Do governing institutions operate consistently across administrations or are decisions arbitrary and easily reversed? Can investors be confident that the law will be upheld and applied without discrimination? Does the judicial system allow for disputes to be resolved through fair, transparent, and pre-determined processes?

That’s so “meta”

The Chamber didn’t recreate the analytical wheel – it developed a “meta measure” of rule of law for business by combining underlying indicators from several established indices.

The list includes the World Economic Forum’s annual Global Competitiveness Report, the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer, the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, and several World Bank survey and index products including the Doing Business reports that have been long used by governments as roadmaps for reforms. By pulling relevant pieces of these indices, the Chamber computes a composite score to rank 90 markets.

Sunshine is the best disinfectant

Rating and publishing information about the operating conditions in the marketplace can be one of the best ways to shine light on corruption and poor governance, sometimes prompting a healthy competition among governments to show improvements that will attract more businesses.

Increasing all forms of private investment, including foreign direct investment, is critical to sustaining economic growth for most countries. Over the last few years, however, multinational companies have been reducing their foreign direct investments. In 2018, FDI flows dropped 19 percent from to US$1.47 trillion to US$1.2 trillion.

Companies consider many criteria when evaluating where to do business. Respect for rule of law is often a decisive factor over whether companies can or will participate in an overseas market. Without sufficient rule of the law, the risks are too great and the return on investment jeopardized. Having a high degree of confidence in rule of law is clearly correlated with where FDI flows. Other than the large emerging markets of China, Brazil, Russia, Mexico and India, the top recipients of net inflows of FDI between 2000 and 2017 are the same countries that ranked highly on the Global Rule of Law and Business Dashboard.

Room for improvement

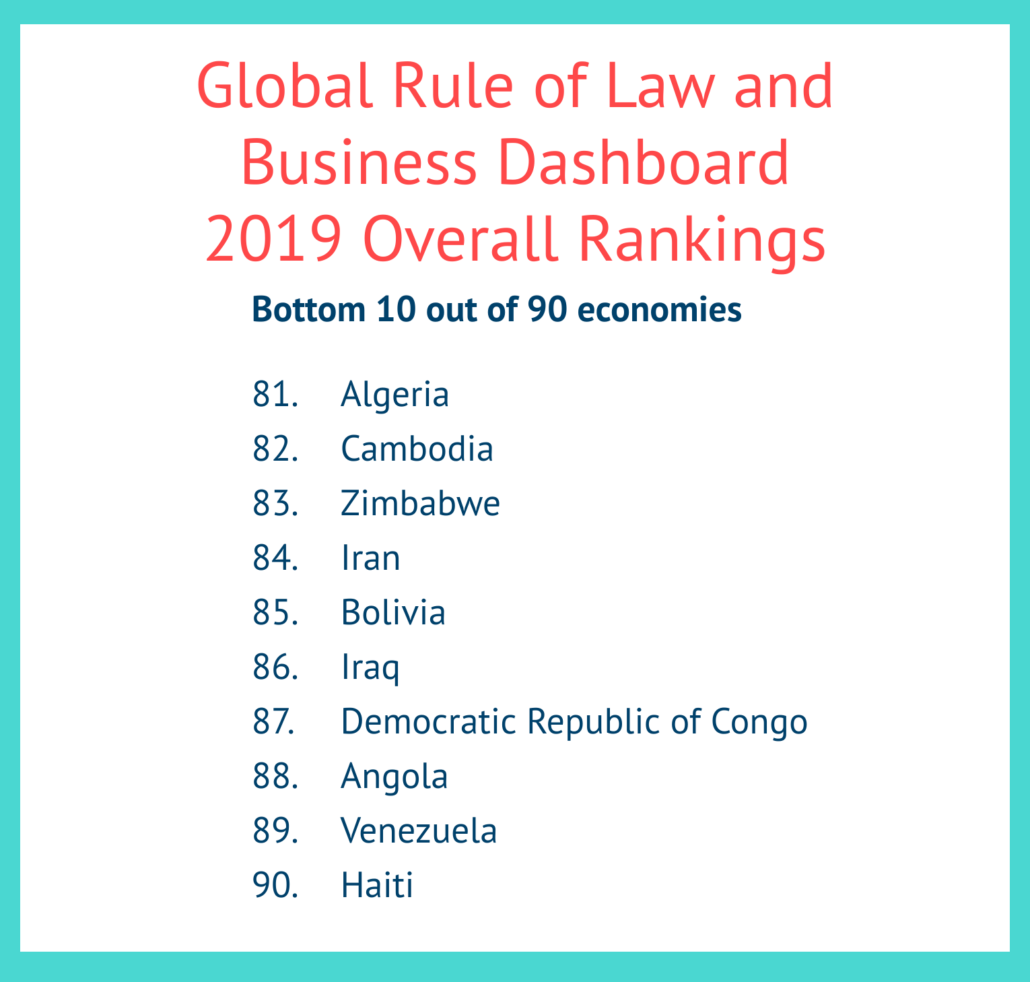

Unsurprisingly, Singapore, Sweden, New Zealand, Netherlands, Australia, Germany, United Kingdom, the United States, Japan and Canada comprise the economies held the top ten slots on the Rule of Law and Business Dashboard released in July 2019. (China fell from 19th in 2017 to 26th in 2019.)

And, unsurprisingly, countries beset by political instability and civil strife remain stuck at the bottom of the index. Here in the Americas neighborhood, Guatemala and Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Mexico are all perilously close to bottom of the list, something we should be concerned with and engage these countries on as important trading partners.

Importantly, the Chamber report points out that, “income is not necessarily a predetermining factor in terms of the strength of the rule of law and business environment.” Senegal and Kenya, with a per capita GDP of just around US$3,458 and US$3,292 respectively, score similarly to South Africa with its per capita income that is almost four times higher.

In producing the study, the Chamber seeks to induce positive changes across the board over the long run. Although the Global Rule of Law and Business Dashboard hasn’t been conducted long enough with a full complement of countries to tout a concrete impact just yet, the Chamber reports that the aggregate score does seem to be moving in right direction, increasing from 51.63 percent in 2015 to 56.77 percent in 2019. Even the United States pulled its score up more than four percentage points from 2017.

The best kind of competition

Benchmarking is a valuable approach, not merely to expose flaws but as a way for governments to identify and adopt reforms yielding proven results for other countries. Governments can even market an improved ranking to potential investors.

While we often measure the outcomes of trade agreements by the volume of trade, the biggest victory may be the least appreciated: the subtle but important improvements to the way our trading partners respect the rule of law as applied to their own citizenry – and to ours.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).