Published 22 August 2023

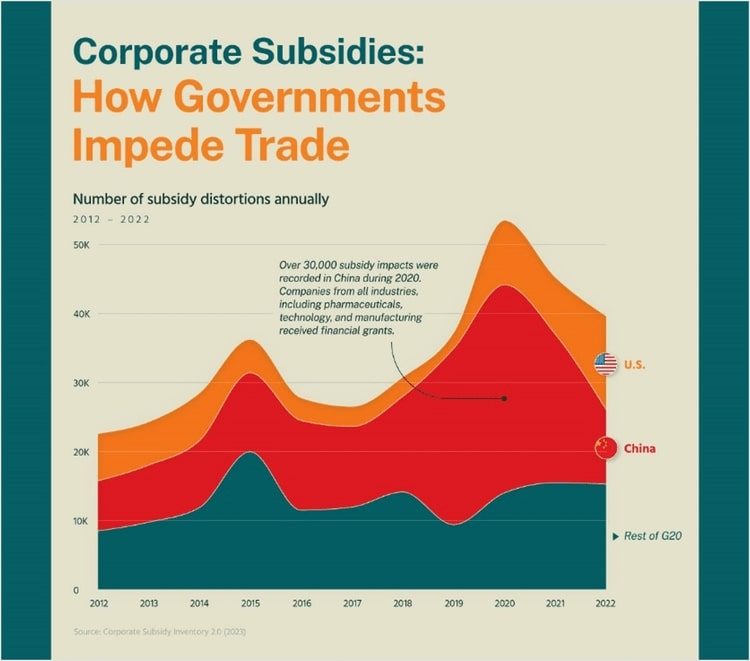

Subsidies have always impeded trade's ability to optimize economic outcomes. But governments are increasingly using them as a weapon of geoeconomic statecraft. In this graphic, the final in our series "The Age of Trade Fragmentation", we asked Visual Capitalist to show how – and by how much – the governments of G20 nations have deployed corporate subsidies since 2008.

(Text by Chuin Wei Yap)

Do governments pick corporate winners?

The answer seems obvious. In the US, in the last 30 years, Washington-funded defense-related research helped to mint corporate winners. The US government used its attorneys to help Intel Inc. break its fast-rising chip rival Japan in the 1980s. Japan itself never was particularly shy about its use of industrial policy. In Europe, Renault and Volkswagen were famously state-owned national champions.

China says it doesn’t “unfairly” subsize exports or national champions. The scale of its subsidies, however, has over the last two decades increasingly become the subject of international trade disputes. By giving away cheap or free land, tax rebates, loan support, or just straight-up cash handouts, China nurtured global behemoths and flooded global markets, showering $27 billion on energy subsidies on its steel champions, $33 billion on its paper producers, and at least $75 billion on the tech titan Huawei Technologies.

Our friends at Global Trade Alert, in a 2021 report we co-sponsored, began the formidable task of tracking and compiling just how much subsidies the world’s governments give out. They pursued this project in a common understanding with us that subsidies are inherently detrimental to global trade. Subsidies impede reciprocity. They impair trust between trading partners. They stoke public skepticism in the mutual benefits of trade.

As Visual Capitalist shows in this illustration, the final instalment in our series ‘The Age of Trade Fragmentation’, the world’s biggest economies still are its biggest subsidizers. And, according to Simon Evenett’s continued research on the subject at Global Trade Alert released earlier this year, China takes the lion’s share of global subsidy distortions since 2008, trailed by the US and Europe as a whole.

The level of global subsidies has ebbed slightly after spiking to an all-time record during the pandemic, but still remains at very high historical levels, data from Global Trade Alert’s Corporate Subsidies Inventory 2.0 shows.

Yet such subsidies remain manifestly ineffective. Ten years ago, Chinese-listed giants received US$14 billion in subsidies, a 23% increase year-on-year, even when their collective profits rose less than 1%, a Wall Street Journal report showed.

In a December 2022 paper for the Washington-based National Bureau of Economic Research, ‘Government Subsidies and Firm Productivity in China’, co-authors Lee Branstetter, Guangwei Li, and Mengjia Ren show that Chinese subsidies could not produce corporate winners. The authors in fact found that the larger the subsidies received, the lower the recipient firm’s productivity. Even subsidies given out in the name of research and development didn’t seem to bump up productivity growth, they said in a study spanning 2007 to 2018 – though subsidies did create more jobs.

Increasingly prescriptive industrial policy is not going away anytime soon. There’s no secret that the world is in the grip of a new subsidy contest among nations. It’s another sign that governments continue to impede trade even as they say they mean to facilitate it. “Such subsidies have been a source of tension between nations, irrespective of whether they are geopolitical allies or rivals,” Evenett and Fernando Martin Espejo write. Visual Capitalist rounds the findings out with a Voronoi. Check it out.

© The Hinrich Foundation. See our website Terms and conditions for our copyright and reprint policy. All statements of fact and the views, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author(s).